THE NEW YORK TIMES

By JOSEPH BERGER

Piri Thomas, the writer and poet whose 1967 memoir, “Down These Mean Streets,” chronicled his tough childhood in Spanish Harlem and the outlaw years that followed and became a classic portrait of ghetto life, died on Monday at his home in El Cerrito, Calif. He was 83.

Tyrone Dukes/The New York Times

Piri Thomas in 1971. His memoir was an influential portrait of life in Spanish Harlem.

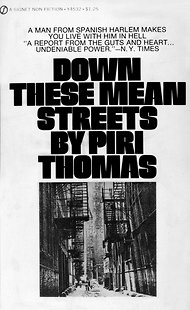

Signet Books

The 1967 memoir, “Down These Mean Streets,” was a best seller and eventually a staple on high school and college reading lists.

The cause was pneumonia, his wife, Suzie Dod Thomas, said.

The memoir, a best seller and eventually a staple on high school and college reading lists, appeared as Americans seemed to be awakening to the rough cultures that poverty and racism were breeding in cities. A new literary genre had cropped up to explore those conditions, in books like “Manchild in the Promised Land,” by Claude Brown, and “The Autobiography of Malcolm X.”

“Down These Mean Streets” joined that list. The memoir, Mr. Thomas wrote on his Web site, had “exploded out of my guts in an outpouring of long suppressed hurts and angers that had boiled over into an ice-cold rage.”

The novelist Daniel Stern, reviewing the book in The New York Times, called it “another stanza in the passionate poem of color and color-hatred being written today.”

In the memoir, Mr. Thomas described how he was brought up as the only dark-skinned child among seven children, the son of a Puerto Rican mother, Dolores Montañez, and a Cuban father, Juan Tomás de la Cruz. His dark skin, Mr. Thomas recalled, made him feel like an outlier in his own family and neighborhood, where he was taunted about this looks. Even his father, he felt, preferred his lighter-skinned children.

He described the bravado, or “machismo,” that he affected on the streets. Protecting his “rep” led him to “waste” people who insulted him, he wrote. He sniffed “horse” — heroin — even though he knew the consequences. “The world of street belonged to the kid alone,” he wrote. “There he could earn his own rights, prestige, his good-o stick of living. It was like being a knight of old, like being 10 feet tall.”

As a merchant seaman in the Jim Crow South, he wrote, he persuaded a white prostitute to sleep with him because, he told her, he was really Puerto Rican, not black. He then enjoyed stunning her by telling her she had just slept with a black man.

He returned home while his mother was dying in a poor people’s ward at Metropolitan Hospital and resumed his old ways — selling and using drugs and robbing people. In one holdup he wounded a police officer and landed in prison for seven years, a harrowing time he vividly evoked. It was in prison that he finished high school and began thinking about writing. He found, he wrote, that words could be used as bullets or butterflies. He called writing “the Flow.”

“It came very naturally,” he told an interviewer. “I promised God that if he didn’t let me die in prison, I would use the Flow.”

The book, with its harsh language and scenes, was banned by some schools but soon became assigned reading in many others. The poet Martin Espada said its influence was enormous.

“Because he became a writer, many of us became writers,” Mr. Espada said. “Before ‘Down These Mean Streets,’ we could not find a book by a Puerto Rican writer in the English language about the experience of that community, in that voice, with that tone and subject matter.”

Carolina González, a professor of literature at Rutgers University, said her students continue to find the book “very immediate and descriptive of their lives.”

After the memoir Mr. Thomas spent much of the rest of his life lecturing about it. He also wrote two novels, “Savior, Savior, Hold My Hand” (1972) and “Seven Long Times” (1974), several plays and the collection “Stories From El Barrio” (1979). He also set his poetry to music.

John Peter Thomas was born on Sept. 30, 1928, in Harlem Hospital, where he was given the Anglo-Saxon name. “They wanted to assimilate me,” he said in an interview in 1995. “Whoever heard of a Puerto Rican named John Peter Thomas?” His mother called him Piri.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by two sons, Peter Stacker and Ricardo Thomas; four daughters, SanDee Thomas, Raina Thomas, Tanee Thomas and Renee Shank; three stepchildren, Michael and Laura Olenick, and David Elder; seven grandchildren; and two step-grandchildren.

Despite Mr. Thomas’s hardships, Olga Luz Tirado, his onetime publicist, said he had retained a sense of humor. She recalled taking him to a reading in Brooklyn in the 1990s. “On the way back I took a wrong turn and said to him, ‘Piri, I think we’re lost,’ ” she told a reporter. “He asked, ‘We got gas?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ And he said: ‘We ain’t lost. We just sightseeing!’ ”