From the Culture Kitchen blog

I cannot understand the brouhaha in some circles on the left around Sonia Sotomayor’s description of her parents as “immigrants”. And I certainly cannot believe that people on the right are so petty as to not call her the first “Hipanic”/Latina to the Supreme Court by calling Benjamin Cardozo, a man of Portuguese ascendancy, “Hipanic”.

Many of my readers know how I feel about the word “Hispanic”, so let me put this to rest: The census document quoted in my infamous article expressely describes the word “Hipanic” as used by the agency to describe Puerto Rican and other Americans of Latin American origins who did fall into the category of Mexicans. Citizens of Spaniards and Portuguese backgrounds were not “Hipanics” because they were Europeans. Same with Spanish and Portuguese -speaking African and Asian immigrants.

So people, let’s lay this one to rest: Benjamin Cardozo is not a Hispanic or Latino. Period.

Yet let me get to the issue of whether Puerto Ricans can be called immigrants.

I am appalled that in some mailing lists used by liberal bloggers there’s a rush to accuse right-wing commentators and even Sonia Sotomayor herself for calling her parents “Puerto Rican immigrants”. The logic behind this? That since Puerto Rico is a colony of the United States where Puerto Ricans have US citizenship, that this invalidates calling Puerto Rico a “foreign country” and it’s people as “immigrants to the United States”. The fight is to accuse the right of smearing her parents with the word immigrants because Puerto Ricans, allegedly, have no immigrant experience.

And what baffles me most is that the people pushing this line of thinking are “immigration activists” for whom it is a nuisance to fit Puerto Ricans in their “comprehensive immigration reform” narrative. In the past few years all the talk of immigration laws has been about how it is used to attack Mexicans and other mostly Central Americans. Yet the reality is very different.

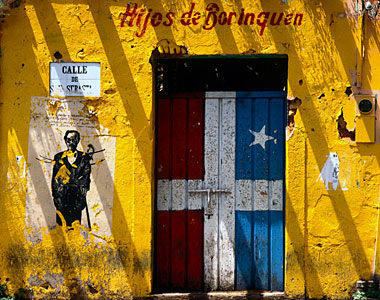

You may want to call Puerto Ricans “migrants” because they we live in a US territory, but the peculiar political status of Puerto Rico as a pseudo-“Free Associated State” (aka: Commonwealth) has made many define Puerto Rican identity in the United States as one of immigrants with no immigrant status.

Rene Marques’ La Carreta (the Oxcart) became in the middle of the 20th century “the play” that captured this migrant/immigrant ethos of the Puerto Rican experience. In the play, a family of sugar-cane field workers sets out of the plantation looking for a better life. They not only end in a slum when in San Juan, but their penury there pushes them to New York City, where they only find ruin, despair and a death that returns them to the land they had previously fled from.

The play became an allegory for Puerto Rican identity because it describes the Puerto Rican experience as one that is fundamentally migrant inside the island and immigrant when in the United States. Rene Marques’ neo-realist theater was cemented in history and in this case, in the historical context of Puerto Ricans being a nation of immigrants.

Many of the boricuas of the 20th century were descendants of immigrants themselves. Spain had given to many Europeans indentured labor contracts for settling in Puerto Rico back in the 19th Century. Through these contracts the King of Spain leased the land to whomever wanted to work it and buy it back with their revenues. Many non-Spanish speaking Spaniards ended in the country, especially Catalanes, Basques, Canarinos and Gallegos along with other European groups like Italians, Irish, along with Roma from many Eastern European countries. Even under Spanish rule Central land South Native Americans were imported as the preferred group of household servants for the Spanish elite.

Even though the task of defining what it was to be a Puerto Rican had been taken up by many artists and thinkers by the time Puerto Rico was invaded by the United States in 1898, the Puerto Rican criollo movement (aka, Spanish/European identified Puerto Ricans) was stronger and more influential than their nationalist counterparts and when compared to the separatist nationalist movement in Cuba and at the other corner of the fallen Spanish colonial world, the Philippines.

It explains in many ways why the United States furiously aligned themselves to these criollistas and unleashed a wave of violence against the mostly brown and black nationalist movement in Puerto Rico; even going as far as torturing the leader of the nationalist movement, Don Pedro Albizu Campos, by using him for radiation experiments.

Yet it’s Puerto Rico’s weird constitutional framework that muddles the migrant/immigrant debate. Here’s the preamble to the Constitution of the Commomwealth of Puerto Rico:

We, the people of Puerto Rico, in order to organize ourselves politically on a fully democratic basis, to promote the general welfare, and to secure for ourselves and our posterity the complete enjoyment of human rights, placing our trust in Almighty God, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the commonwealth which, in the exercise of our natural rights, we now create within our union with the United States of America.

In so doing, we declare:

The democratic system is fundamental to the life of the Puerto Rican community;

We understand that the democratic system of government is one in which the will of the people is the source of public power, the political order is subordinate to the rights of man, and the free participation of the citizen in collective decisions is assured;

We consider as determining factors in our life our citizenship of the United States of America and our aspiration continually to enrich our democratic heritage in the individual and collective enjoyment of its rights and privileges; our loyalty to the principles of the Federal Constitution; the co-existence in Puerto Rico of the two great cultures of the American Hemisphere; our fervor for education; our faith in justice; our devotion to the courageous, industrious, and peaceful way of life; our fidelity to individual human values above and beyond social position, racial differences, and economic interests; and our hope for a better world based on these principles.

I want to stop here a moment because there are no accidents with this preamble: At no point does it say that Puerto Ricans take an oath of loyalty to the United States. At no point does it say that Puerto Rico is part of the United States. On the contrary, this document goes through great pains in defining Puerto Rico as a separate nation and a separate country without acknowledging Puerto Ricans’ right to self-determination, autonomy and sovereignty. On the contrary, the nation of Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans aspire continually to enrich our democratic heritage in the individual and collective enjoyment of of the rights and privileges that come with having US citizenship.

Can you understand why constitutionally many Puerto Ricans make the case that we are a nation recognized by the United States and thus a separate, albeit not foreign country?

And it’s this contradiction that defines the Puerto Rico experience in the United States. An experience that even though has been defined by US citizenship since 1917 (Puerto Ricans who emigrated between 1898 and 1917 to the US actually had PR passports), has always been one of emigration to the United States not just migration from the island.

So please, stop wasting time in debating whether it is OK to call Puerto Ricans immigrants. We are. Get over it. Now go and get Sonia Sotomayor confirmed to the Supreme Court.

Further Reading : Puerto Rico: A Colonial Experiment by Raymond Carr is an excellent resource and place to start reading about the development of the Puerto Rican commonwealth. So is Jose Trias Monge’s Puerto Rico: The Trials of the Oldest Colony in the World and Puerto Rico: A Political and Cultural History by Arturo Morales Carrion.

Use this url to link to this page