CIRCA 2007

Conversatorio de las Galerías Prinardi con la cooperación de PRdream.com

Prinardi and Prinardi USA Mission Statement and Webcast Intro:

Prinardi is an international fine art gallery, whose founders have 30 years of experience. Located at the historical Normandie Hotelin San Juan, P.R. The seven floors gallery specializes on Contemporary American, European, Caribbean, and Latin American Art. Recently we expanded our operations to the beautiful city of West Palm Beach in the United States, giving birth to Galerias Prinardi USA.

Our main goal is to create an international center that encourages appreciation and understanding of art and its role in society, through

direct engagement with artists from different regions of this earth common to all. The intensity of our Goal is fully expressed in the title of our opening show in West Palm Beach,” the Universality of Art, Unifying cultures”.

Galerias Prinardi which is at the CIRCA 07 art fair, in collaboration with its partner gallery, Galerias Prinardi USA, and with the wonderful cooperation of PRdream.com, are proud to be part of this interesting web cast that speaks of the “Archipelago of Art”.

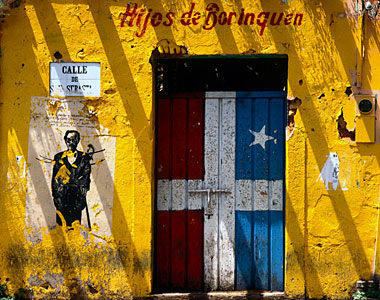

This time we have invited three distinguished artists from the Achipelago Boricua to represent us at Circa 07: Diogenes Ballester,

Martin García and Carlos Santiago.

From within the Archipelago of Florida, USA, comes the Caribbean/Cuban experience. During this webcast and from South Florida in West Palm Beach Prinardi USA will be presenting our show, “Voices of the Caribbean ” with it’s center piece being “Cafetera” an inspiration and creation of Cuban-American Artist Cesar Santalo. “Cafetera” speaks of the Archipelago experience from the Cuban culture experience and how the world perceives it.

In this occasion in following up with our mission of offering the production of audiovisual materials such as DVDs, Television Documentaries and Internet Streaming Video presentations all done a part of an effort to build a solid documented audiovisual library for future generations of Art Collectors, Institutions, Artists and for the public in general to share.

CIRCA 2007

The Fair

The second edition of Circa Puerto Rico, the first international art fair in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean, returns to the Puerto Rico Convention Center, this time during spring of 2007, from March 30th to April 2nd.

Circa Puerto Rico Features a select group of some of the most exiting contemporary galleries in the world. Circa Puerto Rico brings the best of modern and contemporary art to local and international audience of collectors. Featuring such as “In the Spot” a curetted cutting edge artist section, “solo” in which individual artist present special projects, “District Circa” where Art publications present their last editions, and a section for non profit institutions.

The fair also acts as a leader in the island’s art community where an important group of collectors has emerged in the past few ears in response to a burgeoning and dynamic artistic community and a prominent museum and gallery scene.

Set in spectacular San Juan, Circa Puerto Rico combines the best of international art with a stimulating program of cultural events which include: exhibition openings, art workshops, panel discussions, guided visits, book presentations, concerts, performances and video art, for every one from specialized professionals to the general public.

Statement PRdream.com/ Judith Escalona, Moderator

An archipelago exists geologically and later becomes defined politically. Lines are drawn, partitioning a land to make it belong to this country or another with all the historical and cultural consequences. Here today we are positing an archipelago of art — that transgresses or exceeds the political and geographical limits established through time.

Just for the moment then, let us speak of an art archipelago extending from Puerto Rico to Spain, encompassing Palm Beach, Florida and El Barrio, New York City — la cuna de la diaspora puertorriquena — utilizing the web and applying this technology towards artistic ends.

Who are the inhabitants in this archipelago? What kind of art are they producing? What are their cultural references, themes and perspectives? What are their formalistic explorations or aesthetics? ….

IDEA OF THE EARTH BEING SEEN FOR THE FIRST TIME BY MAN AND THE IDEA OF IMAGING THE EARTH AS ONE WORLD WE ALL INHABIT. THIS IDEA OF GEO+GRAPHY

–THE EARTH AND GRAPHICS OR IMAGING OR AESTHETICS IN AN INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT WHICH IS ONE WORLD OF WHICH THIS ARCHIPELAGO IS A PART.

MediaNoche, our gallery, is devoted to new media — digital art in all of its manifestations. Unique among the galleries of New York, it offers exhibition space and residencies to artists working in new media. MediaNoche is a project of PRdream.com, the premiere web site on the history, culture and art of Puerto Rico and the Puerto Rican Diaspora. For more information go to: http://www.medianoche.us and http://www.prdream.com.

San Juan, PR – Palm Beach, FL – El Barrio, NYC

i-Chat: March 30, 2007 at 1 – 3PM

OUTLINE FOR i-CHAT

1. Introduction about the conversatorio by Judith Escalona,moderator 3 min

2. General introduction about each artist in CIRCA: Prinardi Gallery in Puerto Rico, Andrés Marrero, Director, CIRCA 07 Curator Celina Nogueras 6 min

3. General introduction about each artist in Mallorca, Spain. Joan Miro Foundation — 6 min

4. General Introduction about artist in Palm Beach, Florida Prinardi Gallery in West Palm Beach 6 min. Palm Beach Post Art Critic

5. Discussion: 30 min

6. Closing Remarks – NYC – 2 min.

Closing Remarks from Spain — 3 min

Palm Beach — 3 min

San Juan Andrés Marrero, Director — 3 min

7. Closing and acknowledgements — NYC – 1 min

About the Artists

Diógenes Ballester is a visual artist working on paintings, drawings, carvings, engravings and installations. In his work he address ideas related to oral history tradition, ritual, mythology, cultural identity, archeology of memory, and political trans-nationalization.

Diógenes works have been exhibited in the United States, Europe, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. Last year, he presented a simultaneous exhibition at The National Museum of Catholic Art and History in New York City and The Museum of the History of Ponce in Puerto Rico. In this exhibition he incorporates the re-appropriation of cultural artifacts of Ponce and Spanish Harlem to his installations as a way of accessing the past and re-interpreting its presence.

Diógenes recent awards and honors have been the Individual Artists Grant, The New York State Council for the Arts, 2006; Artist-in-Residence Grants, The Museum of the History of Ponce, 2006; and

Artist-in-Residence Grant, The Museum Archive Caribbean University in Puerto Rico, 2007. The Museum of the History of Ponce honored him with a panel discussion on The International Day of Museums and a web cast conversation transmitted between The Caribbean University, the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College and PRDREAM.COM in New York City. He is currently working at his studio in New York City.

Diógenes Ballester is a visual artist working on paintings, drawings, carvings, engravings and installations. In his work he address ideas related to oral history tradition, ritual, mythology, cultural identity, archeology of memory, and political trans-nationalization.

Martin García

Soy Martín García-Rivera, nací en Arecibo, Puerto Rico en el año 1960. Realizo estudios formales en arte desde la escuela superior Trina Padilla de Sanz, en la Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras y la Maestría en Pratt Institute (New York). Actualmente ejerzo la cátedra en artes visuales en la Universidad de Puerto Rico.

Desarrollo mi obra plástica en los medios del dibujo, la pintura y el grabado. He expuesto mis grabados y dibujos en bienales y trienales de prestigio en Europa, América del Sur, Asia, Centro América y el Caribe. He obtenido premios en eventos celebrados en Rusia, Italia, Estados Unidos, Macedonia, España, Suecia y Puerto Rico.

Mi obra representa y es consecuencia de mi identidad como Puertorriqueño.

Actualmente planteo conceptos del dibujo clásico desde el Renacimiento al Expresionismo, asi puedo fundir ideas sobre el laberinto urbano y su tragedia social impuesta a toda nuestra civilización: la violencia, los valores religiosos, el mito, producto del sincretismo cultural y la búsqueda de identidad.

Es la representación de la figura humana eje central de mi expresión.

Las figuras que empleo son metáforas visuales de mis pensamientos acerca de la identidad racial, política, religiosa y diferentes estados psicológicos que adoptamos durante nuestra vida.

El cuerpo humano lo represento en diferentes estados variados de integridad destacándose en ellos el contenido de movimientos, dinamismo y monumentalidad. Como parte de mi proceso de búsqueda tomo apuntes del natural (asi continúo una tradición de más de cinco siglos), también me apropio de imágenes de los medios de comunicación. Utilizo los elementos figurativos sin preocuparme tanto de su significado literal. En ocasiones represento partes deformes y completas del contorno anatómico como una combinación de componentes abstractos y representativos.

Me obsesiona realizar formas simples, llenas de fuerza…energía.

Igualmente en este proceso de búsqueda reinterpreto y replanteo motivos clásicos del arte, distante de su interpretación histórica y del tema.

Todo lo que he observado y estudiado, el mito histórico y el mito cotidiano se añejan en búsqueda de una completa nueva realidad visual, una mitología del presente.

Carlos Santiago, Was born in Peñuelas, Puerto Rico in 1978.

He had his first formal training in the arts in his native town and later moved to San Juan where he graduated from the School of Visual Arts. In 2002 he was awarded the Alfonso Arana’s Scholarship. While attending his grant in Paris, France he studied at the Daniel Fischer workshop and participated in art groups as Le Rat du Champ, and Plástica Latina.

At present, Carlos paintings, drawings and photo montages works are mainly bases on current events. His works are inspired by the emotion generated in him by everything and anything that surround him. His themes include intimate feelings as well as universal fears as war, hunger, violence and how humanity struggle to live a fulfilling life despite its situations and environment. His work has been exhibited in the Caribbean, Latin America, the United States and Europe. It is considered to be a form of expressionism, where his use of intense color with a rhythmical brushstroke places him among the most prominent young artists of the island.

Cesar Santalo was born in Baltimore , Maryland in 1970. At the age of seven he moved to Miami , FL. From a very young age, Cesar has shown to be passionate about art and its creation. By the age of sixteen, he had won many prestigious national art awards and scholarships; including regional and national winner of the Scholastic Art Awards. That same year, the young artist was awarded the Dante Fascell Congressional Art Award and had his work exhibited in the White House. He later received the Art Innovations National Winner at the college level. As a student, Cesar learned from great masters such as Felix Ramos, Ricardo Irisari, Felix Decosio and Manolo Canovacas, His professors are very respected and renowned in their field. Cesar would later attend Pratt Institute in Brooklyn , NY., where he would receive his Bachelors Degree and graduate with honors in Drawing and Painting. During his time in New York he taught at Pratt Institute’s Saturday Art School .

Essays

DIÓGENES BALLESTER:

SEEKING ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE TRANSNATIONALISM

by Shifra M. Goldman

The artist, like the writer, has the obligation to be of use; his painting must be a book that teaches; it must serve to better the human condition; it must castigate evil and exalt virtue.

Francisco Oller 1

Puerto Rican culture is part of my art. My people are descendants of Spaniards, Africans, and Taínos. My formation included the Spanish language with African rhythm and cadence within a Catholic-African spiritualism, between troubadours and their improvised décimas in the vibrant colors of a Caribbean island, facing a sea that incited me to discover the promise of new worlds. These are my roots. And my roots are always present in my art.

Diógenes Ballester 2

Introduction:

Though circumstances and their expression in both art and literature have changed immensely since the days of Puerto Rican painter Francisco Oller (1813-1913), his concepts as well as his art continue to be revered by artists of his nation to this day. Artists and intellectuals of the 19th and early 20th century had to grapple with the effects of colonialism, extreme poverty, strict rules of censorship and the lack of training centers and museums to develop and exhibit their work.

Not until 1950 were conditions favorable for such an undertaking. 3 At that time, the Centro de Arte Puertoriqueño (CAP) was established and definitively changed the direction of Puerto Rican art, aesthetically and thematically. Nevertheless, the underlying philosophy of Francisco Oller remains pertinent to this day: Puerto Rico remains a colony- of the United States rather than Spain; there is still poverty; and censorship still serves as a means of controlling critical expression.

The generation of artists preceding Diógenes Ballester (listed in endnote #2) can testify to these truisms. And, indeed, Puerto Rico remains a colony whose highest ruling official is the Governor, and whose population is split between becoming an independent country or joining the United States as its 51st state.4 Puerto Rico won its independence from Spain with the help of the United States in 1898, as did Cuba and the Philippines, but never achieved national sovereignty as did the others at various times.

Some Pertinent History: The Four Floors

José Luis González’s poetic metaphor of Puerto Rican history and culture, “El país de cuatro pisos” (The Country of Four Floors),5 slices not only through time but through politics, mythologies and class interests, bringing them all together in the present struggles for liberation. As such, it offers a verbal analogy to Ballester’s complex and layered pictorial constructions and lends insight to their iconography.

Speaking in the present tense, González is careful to delineate the three-tiered structure of contemporary Puerto Rico composed, top down, by the U.S. imperialist presence, the dominated upper classes of Puerto Rico, and the lower classes exploited by both. Toward this end, he separates culture into “elite” and “popular,” the latter of which had been studied by dominant class intellectuals only as folklore, thus making invisible the true signification of popular culture in Puerto Rican history.

The “four floors” of the book’s title begin with three historic groups: the aboriginal Taíno Indians whose resistance to Spanish enslavement caused their extermination; the African slaves in the Caribbean and throughout Latin America; and the Spanish conquerors. Contrary to common scholarship, González considers the most important (for economic, social and therefore cultural reasons) to be the Africans. They survived and became carriers not only of their own religious, social and artistic beliefs, but of aboriginal cultural elements due to interchanges between the two most oppressed groups of the social pyramid.

During the first two centuries of conquest, the Spanish population was in a state of flux, therefore the Africans (who could not leave) formed the most stable resident population and their (popular) culture is the first that is “American.” 6 Metaphorically, then, the “first floor” of Puerto Rico is African/Taíno. It is revealing that the earliest acknowledged artist of importance, José Campeche of the 18th century, was the son of a slave nourished by popular culture.

In Spanish Harlem ( New York City), the Puerto Rican artists adopted emblems of the Taíno presence in many of their artworks to give credit to the importance of the first Native Americans of the Caribbean. The politics of African slavery also set the groundwork of all American continental history until the end of the 19th century by which time the European practicioners who had imported slaves by the millions, decided that slavery was no longer a pofitable system. This was started by England and eventually swept the American continent. The last Latin American colony to insist on continuing slavery was Brazil – the largest of Latin American countries – which was conquered by the Portuguese, ruled by the emperor of Portugal, and finally by his son who set himself up as emperor in the New World until he was displaced by the abolition of slavery in 1889, which brought an end to the imperial colonial status of Brazil.

It should not be imagined, however, that the abolition of slavery as an economic structure that had penetrated the entire Western World, aided and abetted by national rulers in Africa, was slowly abolished by anti-slavery forces. A key factor, in my opinion, is the advent of industrialization in Western Europe whose capitalists found it more profitable to set up “industrial slavery” within their own borders and in their colonized Eastern and African nations. Why import slaves for agricultural empires when “wage slaves” were already on hand and employable in factories, mines, and other industries? European peasants were forcibally moved to the cities in great numbers, as the writings of Charles Dickens, and many other authors, testify. In Haiti and the Caribbean, and in many areas of Latin America, however, agricultural production continued well into the 20th century, but it was structured to function as wage labor.

Pertinent to our history as well is the factor of developments in Haiti and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean nations. Too complex to be summarized here, an insightful view of the strong African presence throughout the Americas – economically, socially, and culturally – can be found in the book, Dictionary of Afro-Latin American Civilization, published in 1980 by a professor of Latin American civilizations and linguistics. The imbedded aspects of African languages, religious beliefs, and customs, from the days of slavery to this day, present an astonishing revelation and explain more about modern artists of the Caribbean (for the purposes of this paper) and the Americas as a whole, than many volumes on the subject.7 This information is of particular interest to us, since Diógenes Ballester is the great grandson of Haitian refugees who fled to Puerto Rico and settled at the Playa de Ponce where the family resides to this day. His father (now deceased), from whom he inherited his name, was present in the 1937 Massacre of Ponce during which supporters of Puerto Rican independence scheduled a peaceful demonstration for that independence and for the release from jail of Pedro Albizu Campos, an ardent fighter against U.S. colonial rule. The U.S. colonial governor, General Blanton Winship, ordered the police to fire on the crowd, killing and wounding over 100 people.

Don Pedro Albizu Campos (1891-1965 ) 8 also commanded seven languages – knowledge acquired in seven years of education in the United States and was a good friend of Ballester’s grandfather, Clemente Sagarra, who was descended from the original Haitian refugees that settled in Ponce. Thus our artist, Ballester, has been immersed in the history of Puerto Rico since childhood and, when grown, found it necessary to visit Haiti and also exhibit his work there. Apart from social/political history, it should be noted that Diógenes was educated as both a Puerto Rican and a Catholic – the predominant religion of all Latin Americans under Spanish rule. He considers himself an Afro-Catholic and invokes spirituality from both sources through the titles and visual content of his works of art.

After Haiti (the earliest nation to eliminate slavery on the American continent) came Mexico, which decided on this course after its 1810 revolution against Spain. It is also a matter of historical interest that Simón Bolívar of Venezuela (after whom the nation of Bolivia is named) went to Haiti for shelter and collaboration in his struggle for the liberation of South American colonies from Spain, and was a guest of the first nation which arose against Napolean and the explotation of African slaves. By 1804, the new free Haiti was established and ruled by former African slaves – setting a pattern and model of liberation for the rest of the Americas.

Puerto Rico: Second and Third Floors

The “second floor”of Puerto Rico was constructed and furnished by waves of 19th century immigration including revolutionary refugees from Latin America as well as numerous Europeans. If the first contingent brought ideas of independence to the island, the second expropriated the dominant status from the old landowners. The “third floor” was constituted by the U.S. conquest of Puerto Rico which imposed its cultural paradigm on a population which had not had time to fuse its segments into a national synthesis.

Puerto Rico: the Fourth Floor

The “fourth floor” – and my imaginary “fifth floor”(that of Puerto Ricans in New York) imposed upon José Luis González’s richly conceived housing structure without his permission or knowledge – was erected almost simultaneously. The former resulted in the spectacular and irreparably cracked structure of “late North American capitalism” in tandem with “Puerto Rican opportunistic populism” which weighted down Island society at the end of the 1940s. Organized by Luis Muñoz Marín, Popular Democratic Party leader, who became the first elected Puerto Rican governor, the hopeful expansionist development of “Operation Bootstrap” (manos a la obra) resulted in the modernization (within a dependency mode) that characterized the relations of many Latin American countries in the post-World War II epoch. Since 1917, poverty in the colony had already sent thousands of working class immigrants to the U.S. where they had citizenship but little more access to its privileges than U.S.-born African Americans. Those who were black or dark-skinned suffered racial as well as economic and ethnic discrimination. The eventually negative effects of “Bootstrap” economics can be found in statistics: from the 200,000 Puerto Ricans in New York City in 1948, the year of Muñoz’s election. Migration increased to 612,000 in 1960. The 1990 census might record close to one million. Thus the Puerto Rican population of economic exiles inhabits the “fifth floor” of the four-floor structure. They can, however, move freely between Puerto Rico and the United States which has immense consequences artistically, culturally and economically. Many Puerto Ricans are bilingual and a great many artists have studied in U.S. art schools, while simultaneously North American racism and xenophobia affected the position of all Puerto Ricans in the United States.

Many artists from the Island move back and forth between their country and the U.S. – particularly to East Coast states and Chicago, with perhaps the largest number in New York. Such is definitely the case of Diógenes Ballester, who changed his residence in 1981 and established his home and studio in a section of New York City bordering both the wealthy businesses and Anglo cultural locations of Central Park on the East, and the impoverished dwellings of Harlem which houses African Americans who migrated to New York from the South after the Civil War, but most particularly after World War II began, and jobs were available. The working class Puerto Ricans live in the area known as Spanish Harlem. As we have seen, the name is not a coincidence. Since Puerto Ricans, like other peoples in the Caribbean, reflect a great intermixture with African peoples of the New World, it is natural that they should feel close to the U.S. African population.

In addition, New York’s African Americans, under the leadership of W.E.B. Du Bois, had established not only a political structure in New York, but a powerful and inspirational artistic structure in visual arts, literature, and music. Many historians feel that African-American music (blues, jazz, etc) became the primary original music of the United States replacing a complete dependency on European sources. In additon, white North American musicians like George Gershwin, drew on African American music to create an original fusion that reconstitured the classical music of the United States. It is also well-known that African American music became very popular in France in the early 20th century, opening the doors to all of Europe. Finally, African American musicians of the United States absorbed the rhythms and instruments of Cuba which were also based on strong African sources, and completed the transferences and transnationalisms to which we have been referring. By the late 20th century, not only Puerto Ricans, but large migrations of Cubans and Haitians as well as Dominicans, brought the artistic presences of the Caribbean to the eastern United States. By the time of this reading, the presence of the visual art forms of all these nations is well known in the United States through numberless exhibitions.9

Diógenes Ballester: His Life as an Artist

My first knowledge of and contact with Diógenes Ballester commenced when I attended a graphics Biennial in San Juan. in 1986. Wandering around the exhibition and its premises, I was struck by an amazing homage to a young Puerto Rican artist who was being honored by a sizeable group of people who had just cut a ribbon to open his exhibition to the public. I no longer recall the work presented since Puerto Rico celebrated these events regularly, and I attended many. But I do recall his youthfulness, his friendliness, and his seriousness. In the 1990s, attending New York regularly as a Board member of the College Art Association, I never failed to visit both Harlem and Spanish Harlem, in addition to the more traditional art museums. I quickly learned the nomenclature of Spanish Harlem artists of all varieties: “Ricans, Neo-Ricans, Nuevo Yoricans, Nuyoricans,” and so forth. In addition, as an homage to the Taíno Indians, were terms such as “Boríncan, Borícua, etc. If the name of “Haiti” was adopted from the Taíno language, the term “Borícua” served the same purpose.

Taller Borícua; Museo del Barrio

In fact, the earliest artist-groupings in New York were the Taller Borícua and the Museo del Barrio (neighborhood museum). Both were organized in 1969 as cultural outposts for the Puerto Rican community. Rafael Tufiño, a major printmaker and painter from the Island, designed the first Workshop silkscreen poster. Tufiño worked with Nuyorican and Island artists to translate to New York the collectivist and community service principles of San Juan. Located in Spanish Harlem and boasting outdoor exhibitions, classes for the community, and cultural activities of all sorts, the collaboration between Island and migrant artists is unique.

The main themes of Puerto Rican art can be seen as well in works by Taller artists. Still lifes of tropical plants, the banana as the staff of life ( a focus almost certainly from African sources), and evocations of the aboriginal Taíno Indians, set up important prototypes for Nuyoricans, while one artist’s personal “spirit traps” laid claim to a lost indigenous heritage. West African deities hybridized with Catholic saints, or the ritual attending a child’s burial among African-descent peoples, reactivited another cultural source. Political themes remain cogent to the present. Some works detail abuses of the Island itself and the destructiveness of U.S. military exercises there. Another political expression turned into an art form was the invasion of the Statue of Liberty in the New York Bay by artists who hung a Puerto Rican flag around the sculptured head. A photograph of this event was turned into a color print by Juan Sánchez in 1986. To the photograph he added a large Taíno emblem – of the sort often used by New York’s Puerto Rican artists. Alienation, loneliness, the split and fractured identity, and the search to recover a whole vision of self and existence are the themes of some works, while self-portraits portray interior states of mind. 10

Diógenes in San Francisco: 1995

Like many Puerto Ricans, Ballester has shuttled back and forth between Puerto Rico and the United States, obtaining his art degrees in Puerto Rico and in the United States. Trained in the traditions of realism and surrealism, interested in abstract expressionism and conceptual art, Ballester slowly transformed his art into organic abstraction in which figurative and landscape elements play a role in dynamic and powerful works on a monumental scale. That an active social consciousness is at work is evident:

I use symbolic imagery and organic abstractions to depict the themes of struggle, vulnerability and volition. Intense colors, layers of paint, thick impasto, scratched and blended surfaces create depth, movement and dramatic contrasts which translate the experience of living within the urban landscape of human existence and interchange. 11

At the same time that he reaches outward to U.S. training and formal experimentation (such as computer-generated imagery, film, etc.) Ballester keeps himself firmly anchored in Puerto Rican culture and spiritual beliefs. He remembers that his father made vejigante masks (painted and horned, of papier-mâché) to accompany the brilliant costumes for the famous festivals in Ponce that celebrate Santiago Matamoros (St. James, the Moor Killer). It was in the Ponce Museum that he was exposed to a wide selection of Old Masters, as well as modern and contemporary paintings where Baroque masters Velázquez and Caravaggio, influenced his work, particularly his fascination with chiaroscuro. As an Afro-Puerto Rican, Ballester accepts his country’s cultural celebrations without yielding ground on the manifestations of racism whether they occur in Puerto Rico or the United States.

Caught between two cultures, one of which treats him as the “Other,” Ballester takes these struggles into paintings like “The Anxiety of Life in the Midst of Conflict,” “Struggle Against Racism,” “Confrontation,” “The Struggle Against Alienation,” “Vulnerability: Tied and Liberated Being,” “Portrait of Existence,” “Powerless,” and, finally, “Looking for Structure,” “Compressed Energy,” and “Spiritual Celebration.” In the titles alone, one finds the dialectical ebb and flow between doubt, insecurity, alienation, on the one hand, and the exaltation of the spirit, the energy to transcend the dichotomies between anxiety and hope, between the intellectual and the emotional, on the other. “I live and work in intertwined worlds;” says the artist, “I live and work under the never-ending influences of history, mythology and oral traditions; I live and work in a continuous culmination of today’s diversity.”

Ballester conceives his work in terms of monumental images that push at the borders of his piece, large or small, like that of a frustrated muralist. Many of his paintings are fragments of much bigger ideas that seem not to be exhausted when he finishes creating one. In fact. his working technique is additive: the paintings grow from one sheet of paper or linen to two, four, eight or sixteen, covering an entire wall in his cramped studio. In the process of growth, he changes and overpaints what is no longer compatible with the total composition. The artist’s medium is physical and visceral. He employs the ancient and difficult technique of encaustic – hot wax painting that comes down to us from ancient Greece, that vanished during the medieval and Renaissance periods in favor of tempera and oil paint. Revived in the 18th century, and again in the 20th, its effects, its visual and physical properties, and its range of textural and color possibilities, make it highly suitable for contemporary styles not adequately served by traditional oil painting or the new synthetics. Molten colors are applied with bristle brushes and palette knives; the surface can be opaque or transparent, can be textured in many ways, or can be lightly polished with a cloth to bring out a dull, satiny sheen. If kept warm, free-flowing manipulations may be carried out.

“Paint cooks in Diógenes’ house morning, noon and night,” describes fellow artist Antonio Martorell, “in pots brimming with cadmium yellow, Sienna red, cobalt blue, Prussian and ultramarine blue, Spanish whites and Ivory, blacks, all of them richly mixed pigments spiced with melted virgin wax and applied, still scalding, to the hungry linen.”Adds the artist, “When I stand over my encaustic mix heating in the melting pot, I can see and smell the blending of the crystal damar varnish with the stand oils. I watch and breathe in the fragrant bees’ wax as it coheres with the dry pigment or oil colors. When I apply the mix on the linen surface I am drawn in by its matted mystic magnificence.”

Sensuality is the final aspect to consider in the work of Ballester. It is implicit in his choice of painting techniques and explicit in the work itself. Luminous shadows, convoluted fleshy forms that turn in on themselves like body parts, rotundities, sweeping gestural shapes and stroked surfaces, cavities and bony structures, breast-like forms, warm earth colors and patches like seas and skies, areas bathed in light and shadow, are characteristic.

The encaustic, “Spiritual Symphony” (1994), is an excellent example of his highly suggestive abstract imagery which remains vitalistic and corporeal in form and color. Its origins may lie with pulpy plants, or with fragments of a human body. It either case, they are anchored to the earth below, and the sky above. The artist may be expounding Catholic or animistic spirituality, or both – like varied instruments in his symphony.

“María del Mar” (1993),“Magic of the Camándulas” (or Rosaries) and “The Priest” (both 1994) recognizably articulate the conductors of the symphony: the goddess of the sea, (María/Yemayá, to give her Catholic and Afro-Caribbean names), and those with spiritual power (female and male) who conduct the religious rituals of Puerto Rican espiritismo. To imaginatively record rites he has personally observed in his homeland, Ballester returns to the representational mode for the figures, who emerge arrayed in spectacular vestments.

Diógenes in Paris: Internationalization. the Transnational Americas

In 2000, the Taller Borícua of New York, of which Diógenes Ballester was (and is) an active and enthusiastic member, undertook to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of its incorporation in 1970 with a collectable edition of the Alma Portfolio, one of 100 computer-generated prints on archival paper using archival inks, each print measuring 36”x24”. Headed by Rafael Tufiño, the artists included Diógenes Ballester, Marcos Dimas, Gloria Rodríguez, Fernando Salicrup, Juan Sánchez and Nitza Tufiño. Each work is a diptych with the full print on the left, and a detail to the right with a column for the poetry by Pedro Pietri, Héctor Rivera, María Boncher, Mariposa, Jesús “Papoleto” Melendez, Tania Niomi Ramírez and Juan Sánchez.

A most important element of this portfolio was its experimental character. Fernando Salicrup, having worked for many years with computer-generated digital printmaking, was in a position to assist the artists with this new technique for the portfolio. A clue to the importance of digital production as a new graphic form can be measured by the fact that the 1998 Puerto Rican Biennial, under the guidance of Jury President, Diógenes Ballester, devoted an international panel discussion to the topic which was broadcast on the Web under the auspices of the on-line Puerto Rican magazine, El Cuarto Quenepón.

In the course of discussion, various techniques employed in Europe, the Americas and Asia, were detailed. Examples such as the combinations of graphics with photography, with video, with the use of layering (digital collage), with the digital manipulation of the photographs themselves, with the combination of digitals with traditional graphics like mezzotint, with printing on canvas, on aluminum, on Plexiglas, and on acetate, with the registration of movement, with the use of large scale images beyond the possibilities of traditional graphics, etc. Though not mentioned in the presentations, billboards in the United States have been produced digitally for a number of years, and artists have been transferring their own work to outdoor billboards – like the late Cuban artist from New York, Félix González Torres, and Los Angeles Chicano artist, Daniel Martínez – have replaced street murals with billboards. The ability of computers to create imaginary worlds not bound by reality – as demonstrated by Steven Spielberg’s movies – is also available to computer graphics. What is of central interest for our present discussion, is the portfolio entry of Diógenes Ballester. Accompanied by poetry written by his wife, Maria Boncher, which follows below in first person for the artist himself, Ballester produced a double work of art reflecting his experiences in Paris for a period of about two years.

Diógenes Ballester in Paris

I walked today / from arc de triomphe / flanked on either side by international banks / guardians of post-industrial multi-national finance capital / past the grand palais / the petit palais / through the gardens to the Louvre…I continue eastward…chic speciality stores / reminders of the homogenized existence / that is rendering paris/new york/london/tokyo / indistinguishable… I think /of sandal-strapped feet / interacting with materials / that bind the land.

While living temporarily in Paris, Diógenes Ballester’s digital work created, over a base of disparate architectures – domed, flat and framed buildings – a vision of stone monuments, rock-formed circles and the drawing of a medley of human beings, as well as an Indian profile, and three versions of a black woman kneeling in a loose white skirt. In short, a scene where Paris meets the Caribbean. A poignant man’s head in a lower corner, gently contained in a frame of letters reading “Playa de Ponce,” records the artist’s loss of his father. A maze of photographic segments and violent linear evocations push at the boundaries of the work but are held down by the architecture and by fresh earth below in which rests a straw basket – a memory, perhaps, of Haiti. Red and blue circles seem to be either traffic signs, or computer signs when one has trangressed the rules. The poetry diptych positions a photograph of a young woman in a black coat and umbrella (his wife) against a muted image of Parisian architecture. The poem itself is superimposed over the image.

The tremendous importance of this visit by Ballester to the former artistic capital of the Western world (until it was replaced after World War II by New York)12 is that he not only had the opportunity to review the artistic palaces of Paris – where one can review the great masters of European art over the centuries – but that he also had an opportunity to meet living master artists of Latin America – many of whom had made their homes in France during the 20th century. Visiting or living in France (and other parts of Europe such as Italy or Germany) was de rigueur for many Latin American, as well as North American artists even when they returned to their native countries after the experience and training. A number, however, remained in Paris or other cultural centers – though frequently visiting their native countries for reinvigoration and for exhibition.

Ballester’s personal contact with some of these artists left a powerful impression. As a Latin American himself, he could now identify with the entire continent, and thus with the entire world of artistic production during the 20th century which, in the New Millennium, is becoming truly transnational for the first time in the field of artistic production.

FINAL COMMENTS: THE KEEPER OF HISTORY — HOLDER OF DREAMS13

We must accept the fact that the term “African American” is an unrecognized truism for the entire continent. In fact, there is not a single nation in the Americas, from Canada to Uruguay and Argentina that does not have an African-descent population, particularly on their Eastern shores. As a result, the islands of the Atlantic Ocean not only boast such populations, but maintain a myriad of cultural manifestations of distinctly African derivation.

To be finally considered in this brief history – without which we cannot understand or entertain the visual arts of the Americas – including that of Diógenes Ballester who comes from a long history of African America forebears – is the fact that the Europeans, who invaded all parts of the Americas as well as lands in the Pacific Ocean, did not bring many women with them. Thus we have the creation of caste systems in the colonial period which have been recorded in many paintings which meticulousely rendered images of the various intermixtures, known generally in Spanish (and other languages) as mestizaje (mingling, mixing). These paintings, (titled “caste paintings,” undertook to structure society so that power resided with “pure” Europeans, and later with the “creoles” who were born in the New World but did not mix with its native or imported people of color.

The other side of this pictorial culture and aesthetic is the strong maintenance throughout the Americas of cultural expressions derived, embellished, and constantly restructured by the repressed Africans and Native Americans. One of many people who have recorded and described these phenomena – which exist to the present and form the basis of hidden elements in contemporary aesthetics and practices – was Anita Brenner. A North American (born in Mexico in 1906) who spent many years of her life there, she wrote the book Idols Behind Altars: The Story of the Mexican Spirit, in 1929. 14

Stated briefly, her main idea concerned the preservation of pre-Christian religious images and practices by concealing them behind the enforced altars of the conquerors. The term “idols” is, of course a derogatory one; an idea for which Inquisitions were restablished, first in Europe, then in the colonized areas of the world. However it is well known that many indigenous peoples clothed their original “idols” behind the names, demeanors and dress of Catholic saints . Thus they could continue to be worshipped and celebrated without endangering the lives of those who carried on the celebrations. These practices are carried on up to the present.

In terms of Haitian, Puerto Rican, and Cuban peoples, as well as Brazilian – to mention but a few in the Americas and in Caribbean area – the artistic renderings of the “idols,” and the ceremonies that celebrate them, constitute the “idols behind altars.” Carnivals, festivals, processions, dramatic expressions, ceremonies, costuming, music, special clothing, and jewelry, full rich colors and abstracted forms, designate religious activities that predate Christianity, or absorb and restructure it. At the same time these practices are invoked, they also represent a defiance of conquest, slavery, exploitation, racism, and misery through the military and economic intervention of super-national powers and persons. It is to these peoples and ceremonies we must look for that which we encounter in the life and culture of Diógenes Ballester.

ENDNOTES

1. Cited by Puerto Rican artist Juan Sánchez: Rachel Weiss ( ed.) Being American: Essays on Art, Literature and Ldentity From latin America, New York: White Pine Press. 1991, p.96

2. Statement by artist in the 1986 announcement of the Exposición: Séptima Bienal del Grabado Latinoamericano y del Caribe. In this document, Carmen T. Lugo paid the artist the great tribute of adding his name (at 30) to the names of the most illustrious artists of Puerto Rico in the 20th century: Lorenzo Homar, Carlos Raquel Rivera, Rafael Tufiño, Antonio Martorell, Julio Rosado del Valle, Myrna Baéz, Nelson Sambolin, Francisco Rodón. Also included were color reproductions of our works by the artist: The Anxieties of life in the Midst of Conflict (1983); Predella (1984); La Lucha de la Mujer (The Woman Struggle, 1985); Lucha en Contra del Racismo/ Struggle Against Racism (1986), which illustrate his strong social sense – the struggles of women, against racism, anxieties and conflict, etc. The works themselves were powerfully rendered as semi –abstractions utilizing multiple techniques. To this revealing list of titles can be added others of different vintages: The Struggle Against Alienation; Portrait of Vulnerability; Loneliness of the Black Cloud; Spiritual Fluidity; Spiritual Celebration; The Anxieties of Life in the Midst of Conflict; and finally, as an entire category, The Keeper of History, Holder of Dreams, a most revealing and literary title which sums up the poetic tendencies of the Artist.

3. See Mari Carmen Ramírez. Puerto Rican Painting: Between Past and Present, the Squibb Gallery and others, 1987 – 1998, p.14

4. For a more complete history of these issues and their effects on Puerto Rican modern art, see Shifra M. Goldman, “ Under the Sign of the Pava: Puerto Rican Art and Populism in International Context, Dimensions of the Americas: Art and Social Change in Latin America and the United States, Chicago and London; University of Chicago Press, 1994, pp.416-432.

5. El país de cuatro pisos y otros ensayos, Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico: Ediciones Huracán, 1980, pp. 9-90. I am indebted to Samuel A. Román Delgado for bringing this essay to my attention.

6. Point of clarification: the terms “America” or American” as used in this essay refer to the entire American continent. All references to the United Sates refer to “North America” to differentiate this country from the America which lies to the south. I raise this poit because the United Sates of America have appropriated the word to refer only to themselves.

7. Bejamin Nuñez ( and the African Bibliographic Center), Dictionary of Afro-Latin American Civilization, Wesport: Greewood Press, 1980.

8. Pedro Albizu Campos, a brilliant scholar, has been compared to predecessors for liberty like George Washington (U.S.A.), Simón Bolivar (Venenzuela), and Dr. Ramón Emeterio Betances, (Puerto Rico). He is considered the first great theoretician of anti-colonialism. Albizu received a chain of degrees in the U.S. in Humanities, Chemical Egineering, Military Science, and Law. He also commanded seven languages – knowledge acquired in seven years of education in the United States.

9. Many catalogues and Books can be found through galleries, college and universities as well as large libraries in major cities of the United Sates.

10. For an extensive survey of the Puerto Rican artistic presence in the barrio, see the essay by Diógenes Ballester titled “ Aesthetic Development of Puerto Rican Visual Arts in New York as part of the Diaspora: The Epitaph of the Barrio,” in the catalogue Homenaje Alma Boricua: XXX Aniversario, Nerw York:Taller Boricua, Museo de las Americas, 2001-2002, pp.28-29

11. Quoted by Shifra M. Goldman in the catalogue Spirits: Paintings by Diógenes Ballester, San Francisco Calif., Washington Square Gallery, 1995, p.7.

12. See Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom and the Cold War, trans. By Arthur Goldhammer, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983.

13. Title of exhibit for Diógenes Ballester at the Centro Gallery. Hunter College, New York, 2004

14. Anita Brenner, Idols Behind Altars: The Story of the Mexican Spirit, Boston: Beacon Press, 1929/1970.

Diógenes Ballester ends

Martín García

Recapitulaciones: Selección Retrospectiva de Martín García Rivera

Diciembre de 2005

El patrocinio institucional de la Galerías Prinardi y el olfato estético de la curaduría de Martín García Rivera, han permitido el espectáculo de esta selección de obras del artista que recorre los últimos 15 años de su creación plástica. Desde 1978, cuando tomó la primera clase formal de arte hasta hoy, le persigue la misma obsesión por la figura humana y durante estos 27 años, este soporte iconográfico ha sido el medio con el que Martín ha desarrollado su obra como grabador con tal autenticidad y calidad en el oficio, en su contenido y en su propuesta plástica, que ha sido premiada reiteradamente en innumerables eventos internacionales. Pero ese indudable y merecido reconocimiento internacional le ha costado el insilio en su propia tierra. Ostracismo sui generis porque se ejecuta sin salir del País y él lo acoge con la mansedumbre del Sabio, pues como Esquilo, nuestro artista sabe que sólo el que sufre, sabe… Y como sabe, llega a hacerse cómplice de Franz Kafka (1883-1924) en aquello de que para decir la verdad, hay que aceptar el exilio… Sin embargo, la profunda autenticidad y excelencia de su obra, revierte las consecuencias tópicas del que huye o es expulsado, pues, distinto al anonimato de la mayoría de los que lo sufren, el exilio de la obra de nuestro artista ha tenido una itinerancia mundial en la que se ha catapultado su difusión internacional y reconfirmado su excelencia, mientras que, en cambio, esa misma excelencia, llega a convertirse, paradójicamente, en su propio País, en un obstáculo que lo cerca, aislándolo, sometiendo su obra a una criminalización estética aparentemente inexplicable. Se trata de una manera de insilio maleficente pero honroso, orquestado por el liliputismo insularista, por aquellos que aún con haberes propios y meritorios, están resentidos por la envidia ante el estro y la enjundia de su obra, y por la dimensión sombría del mercado del arte, por los Torquemadas inscritos en su circuito, por el llamado árbitro tiránico como lo designó Enrique García Gutiérrez, o el Sistema del Arte como lo califica el transvanguardista Achille Bonito Oliva (1939): una poderosa fuerza perniciosa, ubicua y polifémica que con su mirada panóptica exige tácitamente obediencia a su Canon de rentabilidad, so pena de levantar o continuarle la condena. Pero la cimarronería sabia, valiente de García Rivera a su manera de la erótica del Poder y como si hubiera conocido a Michael Foucault (1926-1984), acepta, (no consiente) la osada criminalización a que se le somete, pues la entiende como realidad convenida y esperada de la lucha diaria con los bajos fondos de nuestra condición humana. Pero como nuestros oscuros fondos ni los inquisidores de la luz que los administran, lo intimidan, Martín se mantiene contumaz, auténtico a sí mismo, perpetuando, radiante y risueño, su verdad y su insilio. Y en esta breve recapitulación de los últimos 15 años de su obra que ahora exhibe la Galerías Prinardi, lo vemos viviendo auténticamente el dominio almirante de su nave y en esta noche de bitácora abierta, atestiguamos las etapas y desembarcos que el ha escogido de su travesía. Atento a las corrientes procelosas y a las hechizantes seducciones del trayecto, tratamos de trazar un posible mapa de este recorrido suyo que mantiene su proa dirigida a un destino abierto…

Primer desembarco

Animinchin (xilografía, 1990) es uno de los primeros desembarcos contestatarios frente a los Torquemadas del marketing que castigan a los que practican la herejía mortal de usar el papel, soporte pecaminoso por “caduco” e “inestable”, al que Martín agrega la blasfemia de manejarlo a grandes dimensiones, cosa que el Canon en su liturgia, sólo permite, so pena de excomunión, al lienzo, al óleo y al acrílico, reduciendo simultáneamente la posibilidad de que su obra sea objeto de consumo. Para esas fechas ya el grabado nacional no era generalmente promocionado y estaba siendo excomulgado por la mercadotecnia y por la incapacidad a la alta ganancia que lo aislaba por el alegado deterioro del soporte (papel) y por la incapacidad para la ganancia exagerada que significaba la multi-originalidad del grabado frente a la expectativa elitista de pagar un alto precio sólo por obras mono-originales. Sin embargo, aquí vemos en respuesta, una pieza de un preciosismo estético y virtuosismo técnico que parece inaudito realizar en unas dimensiones similares a las de un gran lienzo. Pieza hereje en esta ínsula miope, tanto para los mojigatos que conciben la impresión reducida a pequeñas dimensiones, como para los inquisidores del marketing. Sin embargo, ha sido exhibida este año (2005) en Versalles, en una colectiva de artistas Hispanoamericanos y franceses como instalación, mientras el pasado año (1994), obtuvo el Premio de Diploma en la Primera Trienal Internacional de Grabado de Bitola, República de Macedonia, y un premio especial en la Exhibición de Arte Internacional en Petrozavodsk, Rusia, mientras que en 1994, nos representó en la Bienal de Sao Paulo, también como instalación. Esta pieza, de raigambre animista subsahariana, demuestra que cada una de sus partes por separado, como todas ellas en conjunto, se sostienen incuestionablemente, como unidades de una fuerte propuesta plástica mayor, de un preciosismo estético, de un aplomo y una seguridad en la ejecución insuperables que ha revalidado con sendos premios internacionales. En todo caso, Manos Ancestrales (1989) como Piernas Ancestrales (1990) se concibieron inicialmente como piezas independientes, para luego convertirse en partes de una unidad más amplia que pueden asumirse como módulos simbólicos que se transformaron para el ensamblaje del Animinchin (1990) como expusimos en el catálogo de su obra titulada Imágenes en Fuga de 1994. Y que, como apuntamos también entonces, entroncan con las pinturas a escala monumental que exhibiera el alemán Anselm Kiefer en Filadelfia en 1988.

En esta sinopsis de su obra, merece mencionarse igualmente, el díptico gigante Lati-dos (xilografía, 1992), ganador del Premio en la Décima Bienal del Grabado en San Juan en 1993. Su condición de grabado en madera, como sus dimensiones de un grande lienzo, constituyen, junto con el Animinchin, otro gesto cimarrón frente al marketing, mientras son ambas, remate del proceso plástico del dominio del dibujo y del grabado previos, donde aparecen, en distinta concentración las raíces ancestrales de nuestra idiosincrasia. Late la madre, late el feto, laten ambos, en una simbología de equilibrada ecología planetaria, donde el encuentro de dos mundos, conmemorado ese año, se resuelve, como anticipo y realidad, en el mestizaje. Evidentemente, esta obra, se ejecuta, contra el poder panóptico del Polifemo globalizador, con las dotes sobradas que sostienen una obra de dimensiones cimarronas, semejantes a las que ejecutaron sus colegas Dennis Mario Rivera, Luis Alonso, Haydee Landín, Jesús Cardona, Consuelo Gotay, José Peláez, Marta Pérez García, José Alicea y Antonio Martorell para inaugurar el cascarón del Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico en el año 2000, a solicitud de la gestora del proyecto, la profesora Adlín Ríos Rigau. La comisión de estos grabados le incorporaba al Museo yema y clara, pero los miopes chics que lo controlan, lo han convertido, a lomo de un País depauperado, en huevo Fabergé, en caja de resonancia y espectáculo para adornarse.

Se destacan igualmente en esta muestra, Danzarinas Ceremoniales (1995) grabado ganador de un premio en el Decimotercer Premio Internacional de la Incisión de Biella, Italia (1996), distinción que revalida su importancia y calidad en la Segunda Trienal Internacional de Grabado de El Cairo en 1997 con un premio semejante. En esta xilografía se exponen dos planchas de evidente contraste plástico. Ambos desnudos femeninos, contundentes y macizos, en un evidente homenaje a nuestra africanía, están manejados para destacar el espacio positivo y negativo del campo pictórico. El de la izquierda, rodeado de la sutileza del fondo rayado de la veta, contrasta con la maciza saturación del cuerpo que el sutil gris del lomo del muslo, le otorga a la imagen, la voluminosidad de la escultura; mientras que, simultáneamente, la forma queda asiluetada por una línea blanca, quebrada en algunas zonas, difuminada por el frotado en otras, que la destaca del fondo y que ya para entonces, es anticipatoria del tipo de línea blanca que el artista desarrolla en 1995 y que retoma en el 2003, contrastando con la línea de trazo oscuro y expresivo, tan característica de su época anterior. El grabado de la derecha, por su parte, trasmite la total contundencia del volumen escultórico, ayudado por el fondo neutro que logra fortalecer su iconografía al aislarlo, mientras el rayado de la veta, usado como recurso expresivo, crea unas luces que el artista coloca estratégicamente en el pecho, el lomo del muslo, la parte lateral del otro, el glúteo y la cadera, para destacar aún más, la condición volumétrica de la imagen.

Tampoco podemos prescindir de Refiguración I y Refiguración II (1999) y Metamorfosis (2000) con las que participó en la Tercera Trienal Internacional de Grabado de El Cairo en 1999, y en las que reasume y sintetiza de una manera nueva, tal y como indicamos en un artículo en la revista Boricua de Nueva York en el año 2000: los rasgos más destacados de sus grabados en pequeño formato de las últimas dos décadas entre los que se destacan aquellos de una sintonía expresionista hija de los maestros grabadores alemanes como Erich Heckel (1883-1970) y la secuela de alguno de sus continuadores, donde sus formas de líneas duras o quebradas y tensión sobrecogedora conforman el correlato plástico de una temática que, como la expresionista alemana en su momento, conforma una crítica patética del lado oscuro de nuestra condición humana y la angustia que produce y que en este caso, usan de base, el cuento surrealista de Kafka, Metamorfosis. Son ellos, plataforma donde la soberanía del trazo suelto propio de la pintura, semejante al gestual del expresionismo abstracto, se manifiesta aquí, sobreponiéndose y dominando sin obstáculos la dificultad que supone la resistencia de la superficie en un grabado de extracción. Se hace patente aquí, un feliz entrejuego entre el dominio técnico y la voluntad de arte (Kunstwollen) que lo dirige, constatando nuevamente, en este grabador de envergadura internacional, que esto que gozamos perceptivamente, solo puede hacerlo, quien puede, no quien quiere. Sobre su contenido, comentamos entonces: Acaso también éstas tres planchas manifiesten una especie de proceso, como el que manifestó en su serie Mascarada (1989), expuesta en la muestra de Humacao-Carolina, en la que describe los pasos de la aniquilación humana de una narcomaniaca. En cambio, García Rivera se coloca en su antípoda; no expone un proceso de aniquilación sino, en cambio, uno de liberación personal al afirmar su propia identidad o la colectiva; al demostrar (acaso) la especificidad cultural diferenciada de Puerto Rico, que como crisálida se enfrenta al país dirigente de la globalización homogenizadora, por su propio futuro.

Segundo desembarco

Menos de dos años después, para mayo del 2001, después de varias obras de acrílico sobre papel, nuestro artista se desdoblaba. Ponía un alto momentáneo a su producción perita y premiada de grabador, para internarse en el campo del color con la pintura de acrílico. Nuevamente, se mantenía on the move como es típico de los personajes de Kafka y del propio dinamismo interno del artista, pero este dinamismo no se gesta para hacerle cucasmonas al marketing, sino para encauzar un nuevo recurso plástico que le sirva de ámbito a su expresión propia. Pero como nada surge por generación espontánea, a estas obras le preceden exhibiciones de pintura desde la década de los 80. Una de 1980 y otra del 1985 en las que combinaba la estructura insoslayable de racionalidad inherente al dibujo con la pintura que, en su caso, ha tenido siempre hasta ahora como norte, lo esencialmente propio del pigmento: manifestar el espectáculo de sus cualidades sensoriales, incluso un hedonismo cromático que lo acerca a la Transvanguardia, heredado en alguna medida por la vía del expresionismo alemán de principios de siglo pasado asumido excelentemente. Por eso en el catálogo de la exposición Refiguraciones (2001), nominé a este binomio como una aventura Entre el Cielo y el Infierno, cosa que se sostiene sin duda también en el conjunto de obras que expone dos años después.

Tercer desembarco

En noviembre de 2003 el artista expone otra propuesta, en esta ocasión, desbordante, que nombró con el título general de Lenguaje Corporal. Al comentar las 12 obras de gran formato y continuo movimiento de dicha muestra, el que suscribe, añadía en un ensayo sobre dichas piezas que el balance entre lo apolíneo y lo dionisiaco evidente en ellas, no residía en los caminos trillados de la apariencia de las piezas. Evidentemente sobrecogedoras, exponen la cualidad tórrida y bien lograda del mejor lienzo expresionista, como un tratamiento miguelangelesco (y por ende), escultórico del cuerpo que él deserotiza, pues no es su interés seducirnos con esa potencialidad de nuestra condición humana para hacernos consumidores, sino para regalarnos un particular significado plástico y estético. En cambio, el balance entre la polaridad griega tan manida, reside a nuestro entender, en otro registro; en aquella instancia que, como expuse en anterior ocasión, es el resultado, parafraseando al mismo artista, de haberse perdido primero para poder descubrir lo universal que siempre entre los vivos se manifiesta como víspera. En una instancia donde queda disuelta la polaridad entre Apolo y Dionisio, entre el cielo y el infierno, para acceder a la antípoda del vértigo, donde el éxtasis es el soberano, a esa frontera ambivalente entre el cielo y la tierra donde se manifiesta la energía numinosa de la saga siempre inconclusa del verdadero proceso creativo, auténtico porque no copia resultados externos de los procesos ajenos, sino que se embarca en el proceso inédito de su propio viaje interior, hasta toparse con el umbral inédito de la fons vitae… De la Fuente de la Vida que se manifiesta siempre inalcanzable, como víspera perpetua. Y es ahí, al experimentar esa instancia, donde se entiende lo que ha dicho el intuitivo Gaudí (1852-1926): la originalidad es la vuelta al origen.

Cuarto y penúltimo desembarco

Si los anteriores comentarios pueden compendiar la exposición de 2003, la actual exposición de diciembre de 2005, es por su parte, ante el referente de aquella, y en medida considerable, un recorrido sinóptico y meditativo de las recaladas de los viajes anteriores, que el artista ha hecho a vela desplegada. Ahora, en cambio, parece recogerse en una especie de introspección autocrítica y estudiosa del catálogo o inventario de algunas de sus formas significativas previas. Conciente o inconscientemente, vuelve a sus maestros inspiradores, a sus propuestas adaptadas, exponiendo su rizoma de influencias. Me temo, que este recorrido centrípeto al rizoma de sus fuentes, provocará la colisión de las planchas internas de sus profundidades, de la que brotará un nuevo Tsunami plástico en el futuro, acaso como el intenso y arrollador que regaló en la exposición Refiguraciones (2001).

Ahora, mientras tanto, en esta selección retrospectiva, nuestro artista hace un recorrido (un nomadismo que terminaba con la noción de fronteras, como diría Bonito Oliva desde la óptica de la Transvanguardia) de apropiación o adopción por adaptación de aquellos artistas que ofrecen una experiencia formal enriquecedora o pertinente a su sintonía o prioridades plásticas y los adopta y adapta incluyéndose a sí mismo, demostrando en su adaptación, un proceso de encuentro con matices formales inéditos; con los que se ejercita para mantenerse en forma, para mantener en su bitácora, un recuento y dominio de distintos registros formales. Así, cultivando la figura humana como eje de mi obsesión visual, como dice el artista en su exposición en la Liga de Arte de San Juan en 1998, la cualidad escultórica y compositiva de la masa corporal de Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) se nos presenta en Función de su Efecto (1996), mientras recuerda a Edgar Degas (1834-1917) con sus toilettes en la pieza Tan Abstracto como Figurativo (2002) y a Francis Bacon (1909-1992) en el clima fantasmagórico de sus figuras inasibles y de evasivas distorsiones en tránsito (en fuga), con la obra Figura Enigmática (1991). Por su parte, la pieza Se Siente Acosado (2003), es una variante de su propia obra Lenguaje Corporal: Apolo de la Exposición Lenguaje Corporal (2003), pero en este último caso, la imagen resulta más suelta e intensa que la anterior suya, pues como ya lo ha expuesto en otras propuestas, exhibe un manejo expresionista más intenso de push and pull, entre la figura y el campo de fuerzas que rodea, penetra y reverbera el cuerpo desnudo que presenta en tensión y movimiento. Y con ese campo de fuerzas García Rivera confirma en su obra, lo que Pierre Francastel (1900-1970) identifica en aquel que era para entonces arte contemporáneo, campo de fuerzas que se alejaba y contradecía a la cosmovisión renacentista que tenía la caja estereoscópica como símbolo definitorio.

Correspondientes a la lucha de los campos de fuerza son las piezas Autodefensa con Amarillo (2002), Coraza Protectora con Amarillo (2002), En su Particular Pesadilla (2002) y Criatura Tímida en Amarillo (2002). Presenciamos no obstante, una propuesta estética más atenida a sutilezas detectadas por los entendidos, que al efecto y tensión más dramático y evidente de otras piezas de esta exposición (como por ejemplo, la Figuración: El Motivo (1998) en la vena colorista del expresionismo de Die Brücke pero con un manejo más abstractivo del desnudo) a la que se adscriben incluso, otras piezas de exposiciones anteriores. Nos referimos a un experimento formal en su caso, eficaz y logrado, entre dibujo suelto siempre, gestual y eficacísimo, y las manchas amarillas como zonas abstractas de contraste cromático y tensión formal. En el caso de la pieza En su Particular Pesadilla, a la concepción maciza y rotunda del cuerpo ejecutado con los mínimos elementos, le sobrepone la masa amarilla del trazo gestual que ocupa el espacio dejado a la luz en la esquina superior izquierda y su costado, compensada con el tenso balance cromático de otra mancha más limitada, diluida y menos intensa colocada en la esquina inferior derecha de la pieza. En contraste, el proceso manifiesto en la pieza Criatura Tímida en Amarillo, es el inverso: la mancha de pigmento se crea primero y se coloca soberana en el campo plástico como entidad autónoma, convirtiéndose en referente plástico inicial y en reto que obliga a descubrir o acomodar la forma o perspectiva corporal que mejor corresponda a enfatizar el campo de fuerzas. Con estas piezas, García Rivera entra en un proceso más intenso de simplificación formal, ayudado por un particular trazo diluido del dibujo, mezcla tinta china, acrílico y agua, hasta llegar a la frontera de la abstracción casi cubista, mientras el dibujo de trazos certeros y no menos espontáneos, entiende soberbiamente esa anatomía plenamente captada hasta llevarla a su máxima simplificación recapituladora. Todo ello para recalcar sobre el soporte, en este caso, el papel, una realidad plástica de una particular sutileza estética que coincide con la definición que hace Maurice Denis (1870-1943) en 1890 sobre el llamado arte contemporáneo de entonces. En la pieza que nos ocupa, esa sutileza estética que logra dentro de este campo de fuerzas, reside en la tensión plástica entre el elemento formal cromático y la representación corporal que en muchos de los episodios de la pintura expresionista de García Rivera, entendemos ha sido el logro de su propuesta estética unificadora.

Finalmente, quisiera aproximarme a un fenómeno constante en la plástica del artista que a estas alturas de su creación plástica no debemos dejar de puntualizar: nos referimos a la particular relación del artista con las formas que crea. Sobre el proceso al que intentamos aproximarnos, oigamos al propio García Rivera en 1998: Medito lo que quiero proyectar. Observo la figura e internalizo su forma; así permito que el trance, el instinto, el automatismo, sirvan de dirección sobre la superficie. Hay que perderse para poder descubrir. También para añadir más significado a este ritual, cierro los ojos dejando que el recuerdo, la memoria de la forma dentro y fuera de mí se refigure sobre la superficie (énfasis nuestro). El proceso creativo descrito por García Rivera, pone al descubierto, a nuestro entender, lo que Alfonso López Quintás (1928), desde una perspectiva antropológica define como un encuentro: un entreveramiento activo de dos o más realidades (persona con persona, persona con cosa) que son (ambos) centros de iniciativas que ofrecen ciertas posibilidades y pueden recibir las que son ofrecidas. Para ello, es imprescindible cancelar, en lo posible, las distancias, de modo que pueda establecerse un encuentro dialógico, es decir, un diálogo. Y para que lo haya, tiene que haber tanto cercanía como generosidad. La apertura a la generosidad, permite no solo la cercanía, sino, precisamente, por razón de ella, el descubrimiento de las potencias de aquel o de aquello que es objeto de mi apertura, con lo cual, las potencias que se develan, quedan asumidas por el receptor como parte de sus expectativas. Por ende, el otro (en el caso de una persona) o lo otro, (en el caso de un objeto) puede dejar de serlo por virtud de este acercamiento, para convertirse, según López Quintás, en campos de realidades, algo más flexible, delimitable que los objetos.

En la infinidad de los objetos con potencial de convertirse en campos de realidades, podemos incluir, naturalmente, a los géneros plásticos. En consecuencia, éstos pueden convertirse, además, en campos de realidades y por ende, en ámbitos de encuentro por ser fuente inagotable de posibilidades creativas. A nuestro juicio, en García Rivera, como en todo artista radical, los ámbitos de encuentro se manifiestan porque se aúnan tanto la aptitud, esa disposición o habilidad excepcional para manejar los medios plásticos, como el talento, esa capacidad de encontrar a través de ellos. En nuestro caso, la unión en ósmosis recíproca de ambas condiciones, el dominio técnico y la capacidad intuitiva (comprensión pre-racional), convierten el género plástico que García Rivera maneje (el que fuere) en un ámbito: en la instancia, donde según él mismo dice, se pierde para poder descubrir, y dónde se realiza, en consecuencia, un encuentro genuino, porque tanto la aptitud como el talento unificados osmóticamente, se convierten en la herramienta de proyección personal del mensaje. Mensaje que provoca a su vez, como él mismo dice de manera recapituladora, que la memoria de la forma dentro y fuera de él, se refigure en la superficie. Acaso pueda aplicarse aquí, lo que acota recientemente Teresa del Conde, crítica de arte mexicana, de que siempre hay un pensamiento inmemorial inscrito en ”nuestra fábrica interna” (frase de Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) en su Fenomenología de la Percepción). En resumen, Martín utiliza los recursos que maneja porque con ellos puede decir o trasmitir lo que quiere ya que con ellos, ha logrado el ámbito natural de expresión de aquello que descubre. Y, ahí, en el proceso de configuración de la obra de arte, se desdibuja la distancia entre forma y contenido y se hace patente, como lo entiende Arnold Hauser (1892-1978) y Georg Lukács (1885-1971), que el acto creador es la ejecución y no la visión (Peter Ludz (1931), recapitulando las ideas dialogadas entre Hauser y Lukács) pues los medios de representación pierden entonces el carácter de “instrumentos meramente neutrales”para convertirse en elementos constitutivos del acto creador mismo. Con lo que visión artística, contenido, forma y material se funden en una síntesis en el proceso de configuración de la obra de arte (ibid). Por eso, Martín, como Picasso (1881-1973), no se dedica a buscar sino a encontrar: Mi objetivo, ?dice el malagueño universal?, no es mostrar lo que busco sino lo que encuentro, e igual que el más grande latifundista de formas del siglo XX, García Rivera manifiesta, en los pocos lustros de su prolífera y esforzada producción, una dotación proteica, multi-forme para las formas artísticas que, a nuestro entender, parangona a nivel nacional, con el variado catálogo plástico de los octogenarios maestros Julio Rosado del Valle y Augusto Marín; y me arriesgo a pronosticar que puede ser el mismo cauce que parece seguir, con ingente espíritu y seguridad evidentes, la obra todavía breve y en auge del joven Carlos Santiago.

Porque intuye y asume todo ello, García Rivera no cae en la tentación, como apunta Jean Baudrillard (1929), de la promiscuidad de todos los intercambios, y de todos los productos, distanciándose del esperanto estético que alienta la globalización, producto del travestismo que vive de la indistinción entre buscar y encontrar tal y como explicaba el que suscribe, en el catálogo de Estampas Taurinas de Augusto Marín (p.15). Por eso, es que no es el último en la línea de producción, y por ende, no cae en el travestismo de copiar búsquedas o resultados de otros, ni obedece al Canon de ningún centro de emisión, sino que como dice Gaudí está inmerso en la vuelta al origen. Y sucede que, por los ámbitos eficaces de encuentro que crea, es el primero, no el último, en el proceso semiótico de difusión de signos, como apuntamos en un ensayo para la exposición Lenguaje Corporal (2003). Por todo ello, Martín, el intuitivo, detecta y se mantiene a distancia de los cantos de sirena tanto de la Globalización como de la dimensión negativa del Sistema del Arte, pues no duda que uno es hijo del otro, y que ambos se retroalimentan de su propia promiscuidad y necrofilia. En consecuencia, nuestro artista, vinculado a la Vida, se sitúa como pocos en las artes plásticas nacionales, en las antípodas de estos gastados simulacros globalizadores que tienen a muchos creadores plásticos en esta ínsula como a perros sarnosos que se muerden el rabo. Y la lucha esforzada de Martín por su saludable inmunización defensiva, lo conduce a acceder a un ámbito de encuentro propio y cada vez, inédito, permitiendo en su obra la manifestación del kairós: del momento oportuno del desvelamiento estético que se manifiesta como la víspera permanente, nunca agotada, de lo que en última instancia es la Fons Vitae. Y es desde esa Fuente de la Vida, que lucha por abrevar en su Origen, que la obra de Martín García Rivera se devela como signo del arte mayor, regalo del talento del artista y del patrocinio profético de esta Casa. Porque como dijo Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), El talento es una larga paciencia, y como dijo Paul Valéry (1871-1945), La mayor libertad nace del mayor rigor porque lo que se hace sin esfuerzo se hace sin nosotros…

Santiago Román-Ramírez

Noviembre de 2005

Martín García ends

Carlos Santiago: RAGING AND RATIONAL

By Dr. Rubén Alejandro Moreira

Translation by José A. Peláez

According to Octavio Paz, Picasso painted with the haste of a century coming to an end. Carlos Santiago, though beginning a new one, is caught in a similar vortex of production, of paintings that show a rapid maturity, along with an intensity and an aesthetic quality, surprising in a work developed in just a few months. In this show, initiated by Galerías Prinardi and intended to lay a bridge between Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, there’s ample evidence of Carlos’ two seemingly contradictory but harmoniously integrated aspects of his soul: Rationality against rage, reason in a deadly duel with confusion.

If we follow closely the postulates from his earlier bestiary, we find ourselves at the center of human contradictions, conveyed with absolute conviction and a masterful composition constructed with a very loose brush-work. He follows that earlier work with paintings like: Gesture With Rabid Bitch and Bull (Gestual con perra rabiosa y toro), heartily (Con ganas), Digest it (Digiérelo) and With Spurs Showing (Con las espuelas por fuera), all done in 2004. There’s a clear difference in the atmosphere of each of these works, and though violence is a common theme to all of them, they’re diverse in their visual approach. Gestural With Rabid Bitch and Bull, presents the figures of such animals, coexisting among free-form color patches. You can sense the turbulence in the figures, heads formed by nervous strokes, the tits, the fangs and legs almost blurred deliberately, creating a movement or tension. The atmosphere is definitely one of struggle, antagonistic from every angle you look at it. Different genders, different species, but the same rage.

With Heartily, Santiago puts irony and distance between the painting and the spectator. A lone black bull in the midst of a red field: Brute force, charging beast… the artist not only expresses confrontation and challenge within the bull-ring but perhaps sexual premeditation. Every contest is a libidinous undertaking. On the more ironic side, we find a painting like Digest it. The only apparently digestible thing in this work is a banana at the bottom of the painting. The rest of the composition is an atmosphere in between grey and white, invaded by slight patches that recall flies. From a plastic point of view, a dialogue between the figurative and the abstract is established, just as in so many other of Santiago’s work. In a very stark, almost neutral composition, virtually the only figurative object, the banana is questioned by the more abstract part of the painting. Santiago’s rationalization is imposed on us, making us realize the more intellectual aspect of his work.

Rage emerges within the context of this exhibition with sharp edges. With Spurs Showing, is another painting symbolic of the constant fighting and bickering with which we live in our contemporary Puerto Rico. As in other paintings of his personal bestiary, Santiago employs

roosters as his main characters. Here the birds appear to compete in a race, sights set on a distant point, the whites, yellows and reds in turmoil, all with a defiant stance. Even if they’re only running, the very visible spurs suggest that a confrontation may ensue. They can also be symbolic of what has become the Puerto Rican national sport: Politics. That may very well be, because these paintings were manufactured right before elections.