Note: The Natural Resources Committee approved the Puerto Rico Democracy Act of 2009 on the future political status of Puerto Rico last week. This bill was submitted by the island’s resident commissioner, Pedro Pierluisi, who is a member of the pro-statehood New Progressive Paty (PNP). The other three Stateside Puerto Ricans in Congress have not endorsed this bill.

According to this proposal, voters would choose between keeping the island’s commonwealth status, adopted in 1952, or to opt for something different. In the latter case, a second plebiscite would let them decide whether they wanted statehood, independence or independence with a loose association to the United States.

Two of the island’s main parties oppose the proposal as having a pro-statehood bias, and a similar bill that the committee approved in October 2007 has since died. Last week’s committee debate marked the 68th time that the House has debated a bill related to Puerto Rico’s status. Puerto Ricans voted to maintain the island’s current status and rejected statehood in nonbinding referendums in 1967, 1993 and 1998.

Residents of the U.S. Caribbean commonwealth are barred from voting in presidential elections, and their Congressional delegate cannot vote.

We have reprinted below an interesting analysis supporting the statehood position that we thought would be helpful in promoting further debate on this status issue. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of NiLP on this subject and we will seek disseminate commentaries on the other status options.

—Angelo Falcón

Puerto Rican Nationalism and the Drift Towards Statehood

by Arienna Grody, Research Associate

Council on Hemispheric Affairs (July 27, 2009)

Near the Caribbean islands of Hispaniola and Cuba lies another, smaller island, the inhabitants of which have never experienced sovereignty. The arrival of Christopher Columbus [Colón] to its shores in 1493 heralded an era of enslavement and destruction of the native Taíno population at the hands of the Spanish colonial system. Four centuries later, the decadence of the Spanish royalty had significantly weakened the once-formidable imperial structure. The Spanish-American War of 1898 became the capstone of the demise of the Spanish empire and the Treaty of Paris ceded control of several Spanish-held islands to the United States. Of the territorial possessions to change hands in 1898, Puerto Rico is the only one that persists in a state of colonialism to this day.

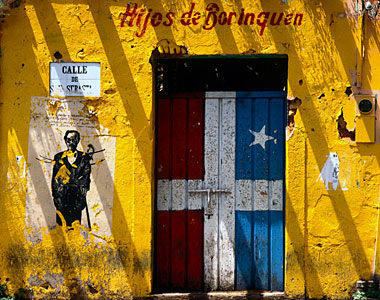

“Puerto Rico has been a colony for an uninterrupted period of over five hundred years,” writes Pedro A. Malavet, a law professor at the University of Florida who has studied the subject extensively. “In modern times, colonialism – the status of a polity with a definable territory that lacks sovereignty because legal [and] political authority is exercised by a peoples distinguishable from the inhabitants of the colonized region – is the only legal status that the isla (island) has known.” Puerto Rico’s legal and political status has not, however, precluded the development of a national ethos. On the contrary, Jorge Duany, a professor of anthropology at the University of Puerto Rico in Rio Piedras, explains that Puerto Ricans “imagine themselves as a nation [although they] do so despite the lack of a strong movement to create a sovereign state.” Furthermore, this perception of a unique Puerto Rican identity had already developed and become established under Spanish rule. Puerto Rican cultural nationalism has persisted through various stages of history, through drives for independence and efforts at assimilation. This puertorriqueñismo is apolitical. In fact, some of the strongest cultural nationalism is exhibited by Puerto Ricans living in the United States.

Nevertheless, the lack of association between puertorriqueñismo and sovereignty, or even of a clearly mobilized independence movement with widespread support, does not diminish the necessity of finding a just and permanent resolution to the question of the status of Puerto Rico.

American Imperialism Called to the Colors

In 1898, the United States won Cuba, Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico from Spain. As U.S. troops invaded Puerto Rico, they proclaimed that their intentions were to overthrow the ruling Spanish authorities, thereby guaranteeing individual freedoms for the inhabitants. However, as Michael González-Cruz, an assistant professor at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez, writes, “the occupation and recolonization of the island did not improve basic rights such as health or labor conditions but rather reinforced the barriers that increased social inequalities among the population.” Although the U.S.’ initial promises of liberation and democracy won the support and assistance of many anti-Spanish Puerto Ricans, it soon became clear that “the United States’ interest in conquering land did not extend to accepting the colonized people as equals.”

Far from promoting the democratic republican ideals associated with the U.S.’ own independence movement and its aftermath, the new colonial regime on the island promptly instituted military rule. It “sought to consolidate its military and economic authority by repressing any activity that might destabilize it or threaten its economic interests.” U.S. military forces protected landowners against the tiznados, or members of secret societies dedicated to the independence of Puerto Rico, rendering the landowners dependent on their presence and rejecting any movement towards sovereignty for the island. Additionally, the period was marked by media repression and censorship as “journalists were systematically pursued, fined and arrested for reporting on the behavior of the troops of the occupation.” These were the first signs that island residents were not going to be treated as the equals of mainland Americans, but they were by no means the last.

The Insular Cases

According to writer, lawyer and political analyst Juan M. García-Passalacqua, the Insular Cases – the series of Supreme Court decisions that ultimately determined the relationships between the United States and its newly acquired territories – “made it clear that the paradigm was the governance of the property of the United States, not of a people.” This point is illuminated by the fact that the Insular Cases primarily addressed tax law. In De Lima v Bidwell (1901), the Court determined that Puerto Rico was not a foreign country – at least for the purpose of import taxes. But in Downes v Bidwell (1901), it held that the island was not part of the U.S. per se. Malavet points to the fact that it gave Congress “almost unfettered discretion to do with Puerto Rico as it wants” as the biggest flaw in the Downes decision.

The decision was neither undisputed nor unqualified. For example, Justice Edward Douglass White concurred, but on the condition that “when the unfitness of particular territory for incorporation is demonstrated the occupation will terminate.” Justice John Marshall Harlan II (best known for his dissent in Plessy v Ferguson (1896)) dissented emphatically, arguing that “the idea that this country may acquire territories anywhere upon the earth, by conquest or treaty, and hold them as mere colonies or provinces, – the people inhabiting them to enjoy only such rights as Congress chooses to accord them, – is wholly inconsistent with the spirit and genious, as well as with the words, of the Constitution.”

Despite these warnings, however, Congress (with the assent of the Supreme Court) continued to construct Puerto Rico as a dependent colonial possession, a status from which, more than a century later, the island has yet to escape. The civilian government introduced under the Foraker Act (1900) was appointed primarily by the president of the United States. The Jones Act (1917) can be said to have bestowed or imposed U.S. citizenship on Puerto Ricans. But this citizenship does not include the full rights guaranteed to citizens in the fifty states. In the case of Balzac v Porto Rico (1922), the Supreme Court held that personal freedoms, while considered a constitutional right on the mainland, were not legal entitlements on the island because of its status as a territory merely “belonging” to the United States, rather than as an “incorporated” territory. Malavet maintains that Balzac “constitutionally constructs the United States citizenship of Puerto Ricans as second class,” affirming Congress’ colonialist agenda and denying Puerto Ricans both the right to self-determination and the option to assimilate on equal grounds.

Americanization

Before Puerto Rico’s destiny to be a colonial possession indefinitely had been sealed, the United States instituted a policy of Americanization, centered on linguistically assimilating the islanders by establishing English as the language of public school instruction. Malavet has described this Anglo-centric agenda as “the most obvious effort to re/construct Puerto Rican identity,” which was made possible by the early view of Puerto Ricans as “overwhelmingly poor, uneducated people who could nonetheless be ‘saved’ by Americanization.” As Amílcar Antonio Barreto, Associate Director of Northeastern University’s Humanities Center, points out, clearly “an implicit assumption underlying Americanization was the presumed superiority of Anglo-American socio-cultural norms and the concurrent inferiority of Puerto Ricans.”

Americanization, although focused primarily on English language instruction to facilitate assimilation, included persecution of the independence movement. Significantly, Puerto Ricans, who had developed a national identity under Spanish rule, rejected the efforts at forced cultural substitution. According to Barreto, the Americanization project “endow[ed] the Spanish language with a political meaning and a social significance it would not have held otherwise,” laying the foundation for a cultural nationalism centered on the Spanish language and heritage.

Economic Dependence

Not only was the U.S.-imposed government unresponsive to cultural demands of the population, it allowed American corporations to control the island’s economy and exploit its resources, effectively plunging it into long-term dependency.

One of the most fateful decisions the government made was to promote sugarcane as a single crop. The dominance of sugarcane production undermined the coffee and tobacco economies in the mountain areas, allowed sugar corporations to monopolize the land and subjected workers to the cane growing cycle, forcing them into debt in the dead season and exacerbating the problems of poverty and inequality already present on the island. Furthermore, “the island became a captive market for North American interests.”

The economic policy of the early 20th century was a disaster for Puerto Rico. Its accomplishments were limited to widening the gap in Puerto Rican society, intensifying poverty on the island and creating the conditions of dependency on the United States from which it has yet to escape.

The Independence Movement

The American indifference to Puerto Rican cultural objectives, political demands and economic needs led to an initially determined drive for independence. One of the most prominent figures of the independence movement was Pedro Albizu Campos. A lawyer and a nationalist, he gained recognition when he defended the sugar workers’ strike of 1934.

The 1934 strike was a response to the wage cuts imposed by U.S. sugar corporations. Faced with a reduction of already marginal incomes, the workers organized a nationwide strike that paralyzed the sugar industry. Albizu Campos took advantage of his position as the primary advocate of the strikers to link the workers’ demands to the struggle for independence.

Albizu Campos based his argument for independence on the fact that Spain had granted Puerto Rico autonomy in 1898, before the Spanish-American War and before the Treaty of Paris. Therefore, he contended that Spain had no right to hand over Puerto Rico to the United States as war plunder. Unfortunately for Puerto Rico, autonomy does not equate to sovereignty. Sovereignty is not a condition that Puerto Rico has ever experienced. But there has been a significant push for an independent Puerto Rico. Nevertheless, this movement has been consistently and violently repressed.

In 1937, a peaceful protest in support of Puerto Rican independence was organized in Ponce. Shortly before the demonstration was to begin, then Governor General Blanton Winship revoked the previously issued permits. Police surrounded the march and, as it began, opened fire on the activists, leaving 21 dead and 200 wounded. The Ponce Massacre is one of the better known examples of the use of violence to silence the independence movement, but by no means was it an isolated event.

Assimilationism

The United States, despite its disregard for the Puerto Rican people, placed a high premium on the use of the island for military purposes. This was highlighted by the location of both the Caribbean and South Atlantic U.S. Naval Commands in the 37,000 acre naval base Roosevelt Roads, which closed in 2004.

The obvious alternative to independence is statehood, an option which entails a certain degree of assimilation. González-Cruz posits that “the extreme economic dependency and the U.S. military presence provide favorable conditions for Puerto Rico to become a state.”

As Governor of Puerto Rico in the 1990s, Pedro Roselló of the Partido Nuevo Progresista (PNP) proposed instituting a form of bilingual education, allegedly because of the advantages associated with both bilingualism and speaking English, but more plausibly to boost the island’s chances of becoming a state. In 1976, President Gerald Ford declared that it was time for Puerto Rico to become fully assimilated as the 51st state. But there was strong opposition, not only from island independentistas, but from American politicians, some of whom were determined to refuse Puerto Rico admission to the union without instituting English as the official language of the island.

In the 1990s, there was lingering xenophobic objection to Puerto Rican statehood as well as echoes of the linguistic intolerance exhibited in the 1970s. The American intransigence on language and assimilation is likely what pushed the Roselló government to try to institute bilingual education on the island.

“Because of the uncertainty of the status question, the proannexationist government […] steered the island toward a neoliberal model in which statehood would not generate additional costs for the United States,” writes González-Cruz. They catered to the U.S. Congress as much as possible in order to try to direct the future of the island toward full incorporation into the United States.

However, this assimilationist push for statehood, embodied by the proposed education reforms was flatly rejected by the population. The Partido Independentista Puertorriqueña (PIP), may have never been able to garner more support than what it needs to barely survive, but assimilation is also perceived by many modern islanders as contrary to the needs, desires and interests of the Puerto Rican people.

Puertorriqueñismo

Puerto Ricans favor neither independence nor assimilation in crushing numbers. They are reluctant to forego the benefits of U.S. citizenship and unwilling to give up their identity as Puerto Ricans. Malavet argues that “cultural assimilation has been and positively will be impossible for the United States to achieve.” This is because Puerto Ricans perceive themselves as “Puerto Ricans first, Americans second.” Yet, in spite of this apparently strong nationalist sentiment, Puerto Ricans reject legal and political independence. In the words of Antonio Amílcar Barreto, “Puerto Ricans are cultural nationalists [but] the island’s economic dependency on the United States […] outweighs other considerations when it comes to voting.”

“Culturally speaking, Puerto Rico now meets most of the objective and subjective characteristics of conventional views of the nation, among them a shared language, territory, and history,” writes Jorge Duany. “Most important, the vast majority of Puerto Ricans imagine themselves as distinct from Americans as well as from other Latin American and Caribbean peoples.”

This cultural nationhood emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries. As more Spaniards were born in Puerto Rico, they developed a distinct criollo cultural identity, inextricably linked to the island. Towards the end of the 19th century, the criollos began to push for greater independence from the distant fatherland. In March 1898, the first autonomous government was established under Spanish rule. Despite its imperfections, the autonomous charter indicated the growing nationalist sentiment on the island. Unfortunately, the United States invaded the island before it was ever granted independence.

Nevertheless, this criollo culture was sufficiently strong and entrenched to withstand the onslaught of the Americanization effort. One side effect of the attempted imposition of American culture and values was the development of a puertorriqueñismo largely defined in terms of anti-Americanism. Rather than simply creating a unique Puerto Rican identity, early nationalists defined Puerto Ricanness strictly in contrast to Americanness. Thus, “Puerto Rican nationalism throughout the 20th century has been characterized by Hispanophilia, anti-Americanism, Negrophobia, androcentrism, homophobia, and, more recently, xenophobia,” writes Duany. To a large extent, this accounts for the rejection of English (or even bilingualism) in favor of Spanish, which is perceived as an important part of contemporary Puerto Rican identity. Even Puerto Ricans living in the United States are often not considered real Puerto Ricans by island nationalists.

Nationhood

Duany describes a nation as “a ‘spiritual principle’ based on shared memories and the cult of a glorious past, as well as the ability to forget certain shameful events.” It is not inextricably linked to statehood. As legal scholar and political leader of the Puerto Rican independence movement Manuel Rodríguez Orellana explains, “Even before the phenomenon of the political unification of nations into states, the French were French and the English were English. Michelangelo was no less Italian than Mussolini.” It is this separation between the concepts of nation and state that allows Puerto Ricans to assert their Puerto Rican nationalism without demanding independence, instead defending their U.S. citizenship.

Although Rodríguez Orellana describes puertorriqueñismo as a “political act on the colonial stage,” it has generally lost its political undercurrents. As Rodríguez Orellana himself says, “the daily life of Puerto Ricans runs, consciously or unconsciously, along the track of their national identity.” Puerto Ricans are always Puerto Ricans. This is not a political act, but a cultural fact. Although independentista intellectuals like the relatively early and highly influential scholar Manuel Maldonado-Denis worry that “the colonization of Puerto Rico under the American flag has meant the gradual erosion of [Puerto Rican] culture” and argue that “Puerto Rico is a country that is threatened at its very roots by the American presence,” the evidence is to the contrary. In fact, migration “has produced an affirmation of puertorriqueñismo as a nationality in the continental United States that is stronger and may be more important than the development of it on the island.” Puerto Ricans clearly continue to exhibit a strong sense of cultural identity and nationalism in spite of their failure to connect it to independence.

A Century of Colonialism

In the words of Maldonado-Denis, “Puerto Ricans are a colonial people with a colonial outlook,” meaning that neither the Puerto Ricans on the island nor Puerto Ricans in the United States have yet achieved “a true ‘decolonization,’ either in the political or in the psychological sense of the word.” In spite of Puerto Rican complacency and in spite of the fact that the United States has managed to design “a process of governance that hides Puerto Rico in plain view,” the colonial relationship that persists between the two polities cannot last forever. 111 years after the acquisition of the island, the time to decide the future of Puerto Rico is overdue.

The Future of Puerto Rico

Malavet identifies the three legitimate postcolonial alternatives for Puerto Rico as independence, non-assimilationist statehood and “a constitutional bilateral form of free association,” arguing that “it is unconstitutional for the United States to remain a colonial power […] for a period of over one hundred years.” The territorial status is only valid as a temporary, transitional status. It must lead to either independence or incorporation.

Given the unacceptability of Puerto Rico’s current colonial legal and political status, the question becomes: what is the best viable option for Puerto Rico?

Independence

García-Passalacqua writes that, “with the reemergence of all sorts of nationalisms, [sovereignty] has become the logical aspiration of any and all peoples in the new world order.” There is no reason why this wouldn’t be true for Puerto Ricans. The $26 billion drained from the island by U.S. corporations each year is sufficient justification to push for separation from the United States. The unequal treatment of island residents, embodied by the phrase “second class citizenship,” provides further grounds for dissociation from the imperial power. Additionally, Puerto Ricans self-identify as a nation.

There appears to be no reason for Puerto Rico to continue as anything other than an independent nation-state. In this vein, then Governor of Puerto Rico, Anibal Acevedo Vila, spoke before the UN General Assembly last year, accusing the Bush administration of denying the island its right to chart its own course and demonstrating a sense of frustration with the aimless direction in which the United States has dragged Puerto Rico. This seems to imply preference for autonomy, if not sovereignty. But while Puerto Ricans certainly insist upon their autonomy, there is no such consensus on independence – that option has never garnered more than five percent of the vote in any of the status plebiscites.

Statehood

Puerto Ricans are not ready to give up their ability to hop across the blue pond on a whim. Despite the fact that the United States continuously exploits the island – its resources and its people – , most Puerto Ricans perceive the benefits of their relationship to the United States as outweighing the costs.

Puerto Rico is “consistently losing its ability to achieve self-sustaining development, and the current economic course” makes it less likely that there will ever be “any significant degree of political and economic sovereignty.” Furthermore, the presence of U.S. military bases on the island reduces the likelihood that the Pentagon would easily let go of the valuable strategic outpost. The greatest opposition to Puerto Rican statehood would come from xenophobic American politicians arguing that Puerto Ricans are inassimilable.

This combination of factors could tilt the balance in favor of statehood over independence. Because Puerto Ricans perceive their economic interests as being tied to their connection to the mainland, they are likely to opt for a status that allows them to maintain the current relationship virtually unaltered. While the majority of island intellectuals may advocate independence, it is important to note that the majority of islanders are not intellectuals.

A New Proposal

Last month, Pedro Pierluisi presented a new bill in the Committee of Natural Resources in the U.S. House of Representatives, seeking authorization from Congress to allow Puerto Rico to conduct a series of plebiscites to determine the preferred future status of the island. However, the bill does not commit Congress to act on the results of the plebiscites and, although it presents Puerto Ricans with and opportunity to choose a reasonable permanent status, it also allows them to perpetuate themselves in an unacceptable state of colonialism indefinitely.

Malavet writes that “perhaps the biggest harm perpetrated by the United States against the people of Puerto Rico can be labeled ‘the crisis of self confidence.’ This form of internalized oppression that afflicts the people of Puerto Rico leads them to conclude that they are incapable of self-government. Under this tragic construct, Puerto Ricans believe that they lack the economic power to succeed as an independent nation – that they lack the intellectual and moral capacity for government.” This U.S.-imposed inferiority complex will almost certainly lead Puerto Ricans to vote against independence if given the option. They have consistently expressed no desire whatsoever to be categorized as a sovereign state.

Because Puerto Ricans do not connect their cultural nationalism to sovereignty and because of the island’s extreme dependency on the United States, the most likely eventual outcome for Puerto Rico will be statehood. Although this is not necessarily the ideal status for the island, it is undeniably preferable to its current second-class existence. What is most important is that the island ceases to be a territorial possession. In the words of Manuel Maldonado-Denis, “colonialism as an institution is dead the world over. Puerto Rico cannot – will not – be the exception to this rule.”

The Hope of a Nation

With any luck, Congress will pass Pierluisi’s bill (or a more forceful version that pushes for change) and Puerto Ricans will be given the opportunity to vote on their future. In spite of the strong cultural nationalism that permeates contemporary Puerto Rican society, the economic benefits of statehood are likely to be the most influential factor in a status vote.

Statehood entails a certain degree of assimilation. For instance, Puerto Rican athletes will now have to compete for spots on the U.S. Olympic team before heading to the international event. This absorption into the United States certainly erodes the sense of Puerto Rican nationhood as Puerto Rico is no longer able to represent itself as a specific entity on a world stage. However, this should not hugely effect the continuation of a thriving Puerto Rican culture distinct from American culture.

Moreover, there are definite advantages to becoming a state, not least the expansion of Medicare and the ability to vote. If the territory joins the Union, it will be nearly impossible for the U.S. to rationalize the perpetuation of the poverty currently found in Puerto Rico.

And if the population decides that the economic benefits of statehood do not outweigh the cultural costs, perhaps the shock of losing their Olympic team will spark a widespread Puerto Rican independence movement.