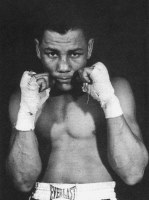

Boxing’s renaissance man Jose Torres commanded ring & respect

by Mike Lupica

For the old-timers, the ones who come out of fight nights at the old Garden and out of a much older New York, it will always be 1965 for Jose Torres, when he was young. It will be the night at the old Garden when he beat Willie Pastrano, dancing and jabbing and finally body-punching his way to a TKO. He became the light-heavyweight champion of the world that night and seemed to have won the championship of the city as well. Jose Torres came from Puerto Rico, but by then he was more here than there.

The next day he made his first stop as champ at 110th and Lexington Ave., climbed up on a fire escape and addressed a crowd of thousands.

“This is for everybody,” he said, and told the crowd that if he could do something like this in the city of New York, anything was possible.

But he was so much more than just a prizefighter, even if that is how the world first knew him. He became the first Latino columnist in town, at least in an English-language paper, when my old boss, the great Paul Sann, put him to work at the old New York Post. He would later become a commentator on television, and radio host, and in the 1980s even became the New York State Athletic Commissioner.

He was a friend to Norman Mailer, who was once brave enough to get into the ring with him, and Pete Hamill. He once said that Pete had given him his first book and how he now owned more than 800 of them, and was confident that “Pete’s responsible for six or seven hundred.” He had a good enough voice to sing a ballad one time on the Ed Sullivan Show.

“I keep telling you,” he used to say to me, “I am more a lover than a fighter.”

Jose Torres wrote books about Muhammad Ali and Mike Tyson, and spent so much time trying to save Tyson from himself and what he called the “parasites” around him. And became a friend to Robert F. Kennedy when Kennedy became the U.S. senator from New York.

Kennedy wanted to learn about the city, to know the city, and not just the avenues of power in Manhattan. So Hamill and the late Jack Newfield became guides for him in those years. So did Jose Torres. They would get in the car at night and drive the neighborhoods of Brooklyn, get out and talk to the people who lived in them. A Kennedy doing this, and the kid from Puerto Rico who had won a silver medal in the ’56 Summer Olympics, won the 160-pound division of the ’58 Golden Gloves, would later end up in the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, N.Y.

And Kennedy and Jose Torres would talk through the night. One of the things they talked about was what Robert Kennedy talked about in speeches in those days, about how within 40 years a man of color would be President. It was why Torres thrilled so much to the run Barack Obama made to the nomination and finally to today, even though he was back in Puerto Rico by last year, there to write and grow old as gracefully as he had fought once.

Pete Hamill said Monday that the last time he talked to Torres, his dear friend of half a century, was 10 days ago.

“It’s amazing, Pete, this country – what a place. What an amazing place,” Torres said to Hamill on the phone that day. He was talking, of course, about Obama.

Jose Torres did not make it to Obama’s inauguration. Did not make it to today. Did not live long enough to hear Obama, whom he believed was the heir to Kennedy’s ideals and compassion and spirit, give his speech today.

Jose Torres died in his sleep early Monday, at the age of 72. He suffered from diabetes and his friends believe that his body was never right after the pounding he took from Tom McNeely, a heavyweight, in Puerto Rico in 1965. It was a non-title fight and Jose ended up winning it, but McNeely brutally worked Jose’s body that night.

Jose finally lost his title to Dick Tiger, a future Hall of Famer the same as Willie Pastrano, the same as Jose. It was some amazing time in their division. Then Tiger beat him a second fight at the Garden, even though that one nearly caused a riot when it was announced that the decision had gone against Jose. He fought twice more after that and then retired.

And this wasn’t the beginning of some slow, sad ending for a retired boxer who had taken too many shots to the head. This was the beginning of a joyful, amazing life, one so well-lived and so well-enjoyed, in the city of New York.

For the next four decades he lectured and wrote his books and became Commissioner Torres finally. His last columns were for El Diario. At the boxing Hall of Fame, he is described this way: “Boxing’s renaissance man.” He was all that, a splendid ambassador for the island of his birth and the city he adopted and of his sport.

He was a lover: of his boxing career, of being a champion, of being a writer, of knowing that books he wrote, in his second language, would be on library shelves forever. More than anything he would have loved Barack Obama’s speech today, about the world Jose Torres imagined once from a fire escape on 110th Street, one where anything really is possible.