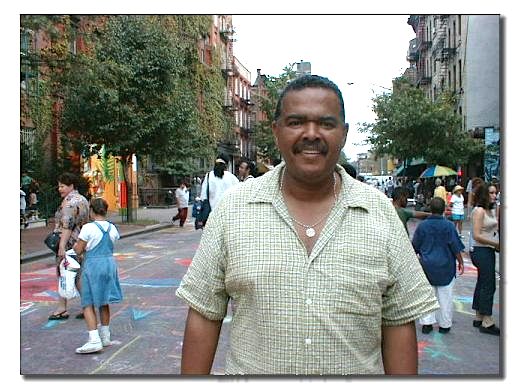

PRdream mourns the passing of Fernando Salicrup, August 6, 1946 – January 1, 2015

Fernando Salicrup was born in El Barrio/Spanish Harlem, where he lived and worked as an artist and cultural entrepreneur. As Executive Director of Taller Boricua (Puerto Rican Workshop), he was instrumental in the development of the arts and cultural corridor in El Barrio.

In the 1980’s, Salicrup was active in providing housing for artists. He spearheaded the renovation of a city-owned public school building and its conversion into the Julia de Burgos Cultural Center, one of the oldest cultural organizations of the historically Puerto Rican/Latino community. The center is the home of Taller Boricua and other art organizations, offering exhibitions and concerts year-round. Salicrup was a member of Manhattan Community Board 11 for several terms.

First and foremost a painter and printmaker, Salicrup worked continuously on his art while advocating for broader social issues impacting the cultural life of his community. His work has been exhibited throughout the United States, Latin America and Europe. In New York City he has shown at El Museo del Barrio, the New Museum of Contemporary Art, and the Bronx Museum of the Arts. The XII San Juan Biennial of Latin American and Caribbean Printmaking.recognized him for his experimental print-making.

He also taught workshops in printmaking and served as a mentor to hundreds of young artists, writers and musicians.

Fernando Salicrup enlisted in the U.S. Marines Corps and served in the Vietnam War. He studied at the Philadelphia Academy of Art and, subsequently, won a scholarship to the New York School of Visual Arts, where he studied painting under Chuck Close and printmaking under Robert Blackburn.

He is survived by his wife of 40 years, Zoraida Salicrup, their sons Fernando Salicrup lll and Danel Salicrup; his daughter Cynthia Blake; and four grandchildren.

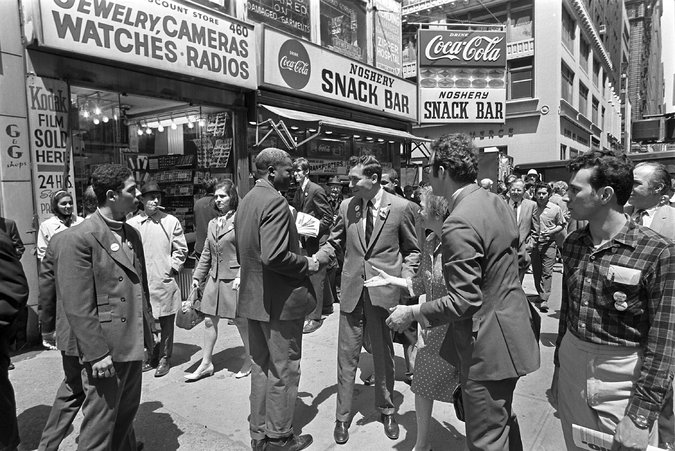

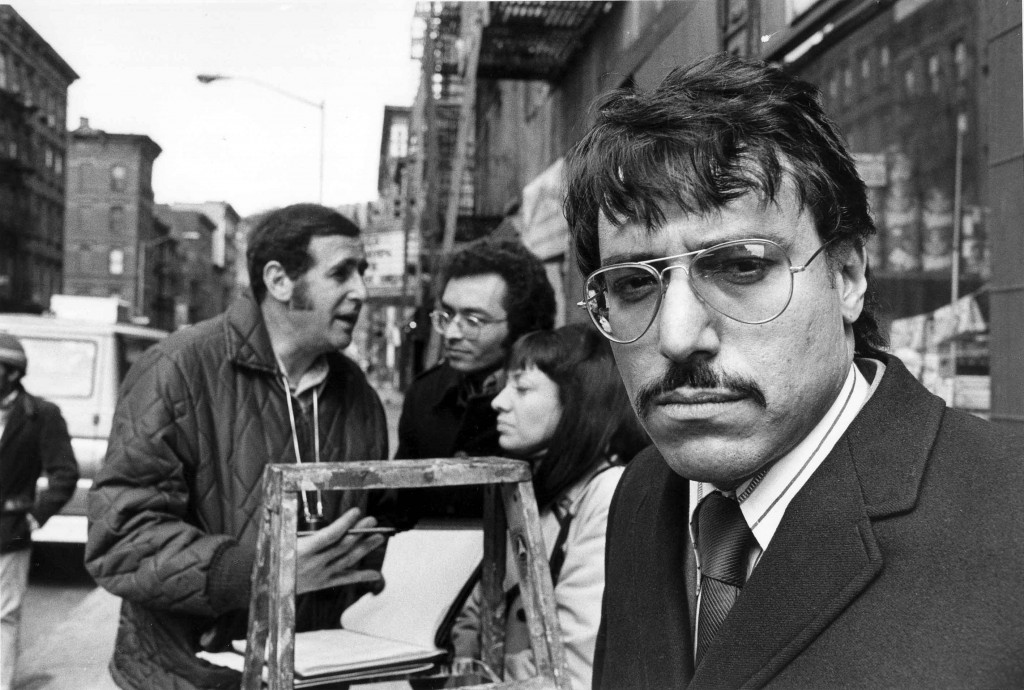

PRdream mourns the passing of Herman Badillo 1929 – 2014

From the New York Times

Herman Badillo, America’s first Puerto Rican-born congressman and a fixture in New York City politics for four decades who championed civil rights, jobs, housing and education reforms, died on Wednesday in Manhattan. He was 85. His death, at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell hospital, was caused by complications of congestive heart failure, his son, David, said.

Mr. Badillo rode many horses on New York’s political merry-go-round from 1962 to 2001. Besides being elected to four terms in Congress, he was a city commissioner, the Bronx borough president, a deputy under Mayor Edward I. Koch, a counsel to Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani, a candidate for state and city comptroller, and a trustee and then board chairman of the City University of New York. But the prize he most coveted — to be New York’s first Puerto Rican mayor — eluded him, despite six tries, in 1969, 1973, 1977, 1985, 1993 and 2001. The ’85 and ’93 bids were so short-lived, they hardly counted, and he never won a major-party endorsement, although he came close in 1973, losing to the city comptroller, Abraham D. Beame, in a Democratic primary runoff. Mr. Beame went on to be elected mayor.

The peaks of Mr. Badillo’s career were his seven years in Congress, in the 1970s, when he advocated urban renewal, antipoverty programs, voting rights and bilingual education, and his leadership of the CUNY board, from 1999 to 2001, when it ended open enrollment in the senior colleges and raised standards for admission, curriculums and graduation after years of academic decline.

He called himself “the first Puerto Rican everything,” and it was true in a way. He was a role model who overcame an impoverished orphaned boyhood and an inability to speak English to become a famous politician. He lost many elections but won respect as a fighter, as the first Puerto Rican city commissioner and borough president, and as the nation’s highest-ranking Puerto Rican officeholder.

Mr. Badillo’s political odyssey was a long arc from Kennedy-style liberalism in the 1960s to Giuliani conservatism in the 1990s. He defied party loyalties and was by turns a Reform Democrat, a Democrat, a Republican and a neoconservative. A lean, broad-shouldered man with a proud, solemn bearing, he often spoke his mind bluntly, sometimes offending ethnic sensibilities and alienating constituents. He called Mr. Koch “cowardly,” for example, and derided Mr. Beame as “a malicious little man” in a 1973 mayoral primary debate. (Mr. Badillo said he had been referring to Mr. Beame’s “pettiness of mind” and not his physical stature. Mr. Beame was 5-foot-2, Mr. Badillo 6-foot-1.)

Mr. Badillo ran for mayor six times. He challenged Michael Bloomberg for the Republican mayoral nomination in 2001. Early on, Mr. Badillo supported bilingual education and assistance for the poor. Later, he concluded that the immigrant’s path to assimilation and prosperity lay in self-reliance, not government largess; he advocated a meritocracy of standard achievement tests, opposed bilingual education and promoted urban renewal to create jobs and housing, even when it displaced poor people.

In the 1990s he became a Republican, Mr. Giuliani’s education adviser and Gov. George E. Pataki’s CUNY chairman. His last hurrah was a 2001 challenge to Michael R. Bloomberg for the Republican mayoral nomination. Even friends called it quixotic, but it reflected the trajectory of a self-made man who had often run the New York City Marathon and always thrived on adversity.

Herman Badillo (pronounced bah-DEE-yoh) was born in Caguas, P.R., on Aug. 21, 1929, the only child of Francisco and Carmen Rivera Badillo. His father, an English teacher, died when Herman was 1 and his mother, when he was 5, both of tuberculosis. Relatives took him in, and at 11 he was sent to New York. Shunted among relatives, he lived in Chicago, in California and with an aunt in East Harlem. He learned English and became an excellent student at Haaren High School in Manhattan. Working as a dishwasher, bowling pinsetter and accountant, he graduated with high honors from City College in 1951 and from Brooklyn Law School as valedictorian in 1954, then settled into law practice in New York.

He married the first of three wives, Norma Lit, in 1949, had one son, and was divorced in 1960. In 1961, he married Irma Deutsch Liebling; she had Alzheimer’s disease and died in 1996. Later that year he married Gail Roberts, who lived with him in Manhattan and East Hampton, N.Y. She and his son survive him.

Mr. Badillo founded an East Harlem Kennedy-for-President committee in 1960 and supported Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr.’s successful antimachine campaign for re-election the next year. The mayor rewarded him, in 1962, with the new post of commissioner of housing relocation.

Mr. Badillo went on to defy Bronx Democratic bosses and win the borough presidency in 1965. He opposed the Vietnam War, backed the presidential candidacies of Robert F. Kennedy and, after Mr. Kennedy’s murder, Senator Eugene J. McCarthy, and won a seat in Congress in 1970. He was re-elected in 1972, 1974 and 1976. But while his political life would continue for 25 years, he never won another election.

He quit his safe congressional seat in 1977, a year early, to become a deputy mayor to Mr. Koch. But they had a falling-out over South Bronx redevelopment, and he departed in 1979. He lost a challenge to Mr. Koch in the 1985 Democratic mayoral primary and a 1986 race as a Democrat for state comptroller. He fared no better as a Republican. He did so poorly in a 1993 mayoral primary campaign against Mr. Giuliani that he quit and became his rival’s Republican-Liberal running mate for city comptroller. He lost again, but Mr. Giuliani won and named him an education counselor.

In his book “One Nation, One Standard: An Ex-Liberal on How Hispanics Can Succeed Just Like Other Immigrant Groups” (2006), Mr. Badillo said Hispanic Americans undervalued education, which he called tragic for the nation’s largest ethnic minority. He was appointed CUNY chairman in 1999, but resigned in 2001 to make his final run for mayor, challenging the billionaire Mr. Bloomberg in the Republican primary. Mr. Giuliani and Mr. Pataki, his erstwhile patrons, backed Mr. Bloomberg, the winner, and Mr. Badillo retired from politics.

LAUNCH PARTY FOR “OUR NUYORICAN THING” by Sam Diaz — Sunday, June 29, 2:00-3:30PM

2Leaf Press author Samuel Diaz Carrion is having his Launch Party for his recently released book, Our Nuyorican Thing, The Birth of a Self-Made Identity on June 29th at 2:00-3:30PM at Taller Boricua in New York City.

Poet, writer and activist Diaz Carrion explores the question, “What is a Nuyorican”? and more in Our Nuyorican Thing. What started out as blog correspondence for the Nuyorican Poets Cafe’s website (2001-2004), quickly turned into a cultural exchange about the Cafe and Puerto Rican culture. Our Nuyorican Thing is a compendium of those blog entries and emails that also include poetry and short prose through the eyes of Diaz Carrion, a “Puerto Rican Indiana Jones” who has quietly studied “the trade route of a new language . . . collecting poetry and stories as the artifacts of the day.” This collection is riveting, informative and delightful, and will satisfy any reader with a cultural appetite. Our Nuyorican Thing’s introduction byPuerto Rican poet, performer, professor, and polemicist, Urayoán Noel.

Please join Samuel Diaz Carrion as he shares his prose and poetry as he enlightens us about the Nuyorican experience.. It will be a night of great poetry, good conversations, and a great way to spend a Sunday afternoon. This event will be hosted by legendary Nuyorican poet, Jesús Papoleto Meléndez. Download the diaz-book-party-flyer and pass it around!

TALLER BORICUA

1680 Lexington Avenue, NYC | 212.831.4333

www.tallerboricua.org

Directions: Subway: 6 Train to 103rd Street

Entrance on Lexington Avenue between 105th and 106th Streets

Center is accessible for individuals with disabilities

“Our Nuyorican Thing” by Sam Diaz

Fascinating book: http://2leafpress.org/online/our-nuyorican-thing/

Sam Diaz, the author, writes about the Nuyorican Poet’s Cafe and how the term Nuyorican went from being derogatory, defining stateside Puerto Ricans, to complimentary, defining an arts and political movement that grew to encompass all ethnicities and nationalities on the margins: The emergent poetry slams and open mics for the spoken word, the true freedom of speech granted to the youth of the voiceless Puerto Rican communities of New York that eventually grew and spread nationally, then internationally to other voiceless communities and their youth.

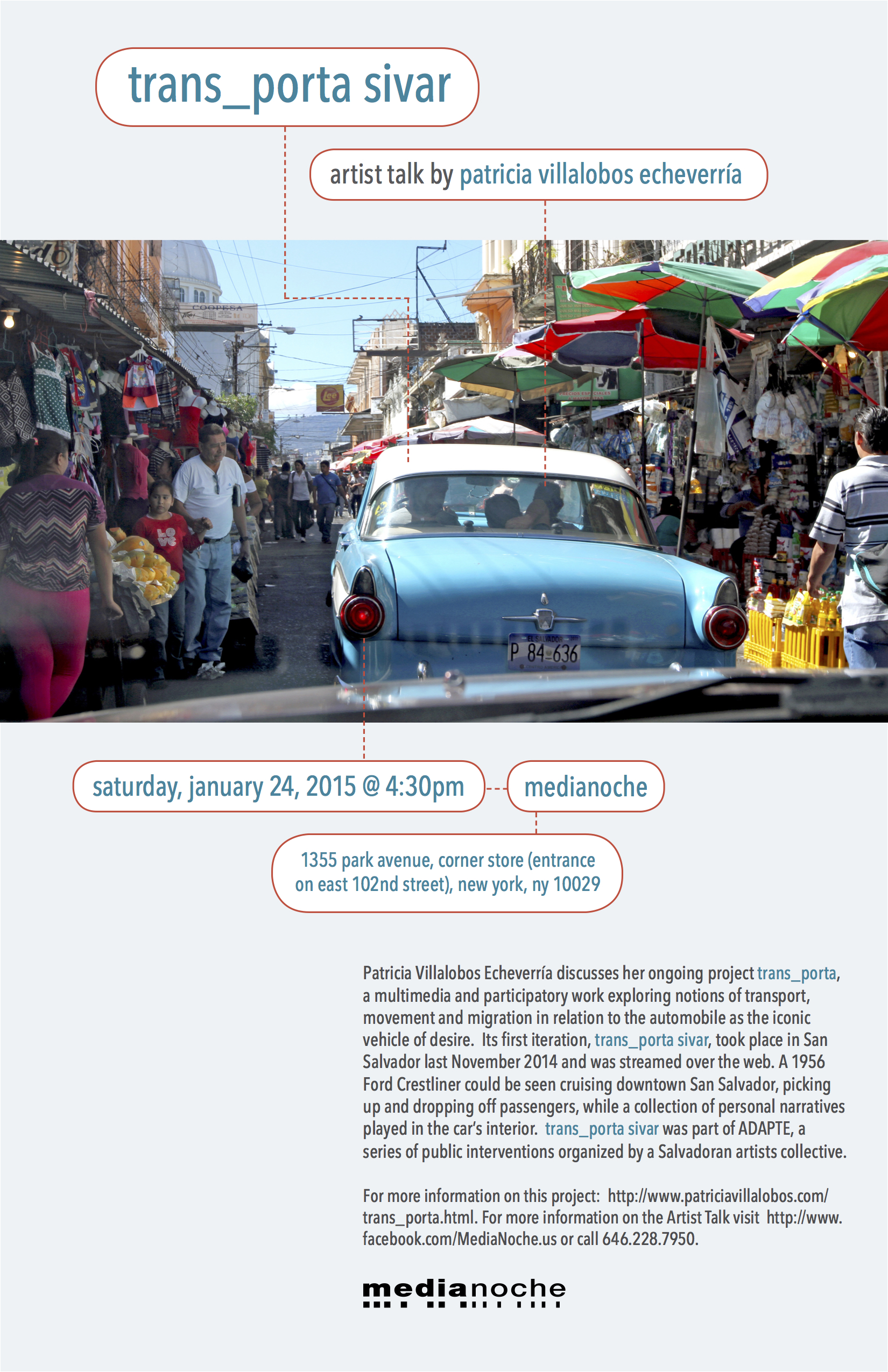

At MediaNoche — “Composition Fukushima 2011” by Kenji Kojima — Opening Reception: Thursday, June 12, 6pm

Kenji Kojima

“Composition Fukushima 2011”

Opening Reception: Thursday, June 12, 6pm – 9pm

Artist Talk: Thursday, June 26, 6pm

Gallery Summer Hours: Thursday, Friday, 6pm – 9pm, and by appointment

MediaNoche

1355 Park Avenue, Corner Store — Entrance on 102nd Street

New York City

www.medianoche.us

info@medianoche.us

http://www.facebook.com/MediaNoche.us

646.228.7950

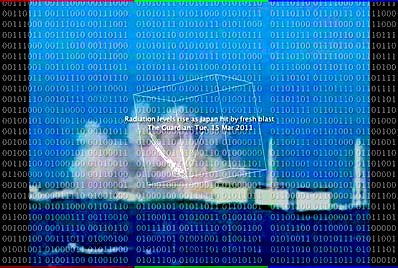

Radiation from the Fukushima nuclear disaster that occurred four years ago, in 2011, continues to contaminate the surrounding area where the plant is located and is spreading beyond Japan.

“Composition Fukushima 2011” is Kenji Kojima’s response to the ongoing nuclear calamity. Online photographs from the international press related to Fukushima and the unfolding events to contain the radiation are accompanied by a soundtrack. But this is no ordinary soundtrack. The music is actually a compilation of musical sequences produced by the images themselves. A kind of transcoding through an algorithm that converts the color data of the images into musical notes, each photograph producing its own melody.

“Composition Fukushima 2011” is also a kind of techno synesthesia and proof positive that aesthetic principles of form, rhythm, symmetry, repetition, proportion, scale, etc. universally apply—here facilitated by the global platform the Internet alone provides. The exhibition is part of a curatorial series at MediaNoche, presenting media projects on environmental issues. Judith Escalona, Director of MediaNoche, curates.

At MediaNoche, wall projections and monitors display redundant images that are sourcing the sonic experience and generating a sense of inescapability from the disaster––lest we forget. According to Kenji Kojima: “The problems caused by the accident at the Fukushima nuclear plant have not been resolved. The nuclear plant is still contaminating the land and sea. Even though exposure to the deadly radiation will continue beyond our lifetime, our attention to this ongoing tragedy is a fading memory. We must recall our experience of the Fukushima disaster and what it means for us all.”

“Composition Fukushima 2011” is a distillation of an earlier project “RGB Music News”, covering the news cycle worldwide with 335 musical sequences and their corresponding news stills for the entire year of 2011.

Artist Bio:

Kenji Kojima is a visual artist whose work spans the centuries in technique and technology. In 1980 he moved to New York from Japan, where he continued painting using egg tempera and techniques from the European Middle Ages–an arduous process requiring careful planning. The advent of the Mac computer allowed Kojima to visualize and plan his egg tempera paintings more effectively. It also sent him in a new direction, authoring software for internet-based artworks.

In 2007, Kojima created the RGB Music series, an interdisciplinary work exploring the relation between images and music. In 2008, as part of the series, the installation “Subway Synesthesia” exhibited in New York City. In 2011 “RGB Music News” featured news photographs visually and musically. The RGB Music series has exhibited in media art festivals worldwide, including Europe, Brazil, and the United States. His work has been cloned and archived at Rhizome in the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York.

About MediaNoche

MediaNoche is the place where art, technology and community converge. We offer artists working in new media exhibition space in order to provoke a dialogue that blurs all lines of marginality and alterity. Unique among art and technology groups, MediaNoche is directly linked to the oldest Latino community of New York City, Spanish Harlem, and has showcased a roster of local and international new media artists.

MediaNoche is a project of PRdream.com and is supported in part with funding from the New York State Council of the Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and private donors. Special thanks: Hugh Mandeville, José Goicuria, Kenneth Bowler, Christopher Dascher, Joann Arroyo, Maria Catoni, Joe Falcon, CUNY-TV, Gus Rosado and Operation Fightback, Inc.

PRdream mourns the passing of Jack Agüeros, 1934 – 2014

We extend our deepest sympathy to the Agüeros family.

Jack Agüeros, 79, a Champion

of El Barrio, Dies

By David Gonzalez

New York Times (May 6, 2014)

Jack Agueros Jack Agüeros was an activist. The term is concise, like his many sonnets, but it hardly captures the expanse of his life, which saw him go from a childhood in East Harlem to defending its Puerto Rican people as an antipoverty official, celebrating its culture by expanding and moving El Museo del Barrio, and memorializing its greatest poet by translating the complete works of Julia de Burgos.

Like many Puerto Rican strivers who came of age in New York City a half-century ago, he had little choice but to deploy his talent on multiple fronts.

“People underestimated him because he was sometimes plain in his projection and personality, but he was daring, a visionary,” said Eva de la O, the head of a chamber music group whose first performance, 34 years ago, was, at Mr. Agüeros’s insistence, at El Museo del Barrio. “Sometimes it looked like he was flying all over the place, but like a bird he knew exactly where he wanted to land and where he needed to plant the seed.”

Mr. Agüeros died on Sunday, at 79, at his home in Manhattan. His family said the cause was complications of Alzheimer’s disease.

Jack Ruben Agüeros was born on Sept. 2, 1934, in East Harlem, to parents who had migrated from Puerto Rico. His father, Joaquín, who had been a police officer in Puerto Rico, worked in factories and as a merchant seaman after coming to New York. His mother, Carmen, was a seamstress.

Books and reading were encouraged in their small apartment, as Mr. Agüeros recalled in “Halfway to Dick and Jane,” an essay he contributed to “The Immigrant Experience,” an anthology that came out in 1971.

“As I became a good reader they bought books for me and never refused me money for their purchase,” he wrote. “My father once built a bookcase for me. It was an important moment, for I had always believed that my father was not too happy about my being a bookworm.”

After graduating from Benjamin Franklin High School, he spent four years in the Air Force. He returned to New York and enrolled at Brooklyn College to study engineering, but a class with the English scholar Bernard Grebanier changed him. He fell in love with literature, especially Shakespeare, and writing.

He began writing plays and poems, though by the time he had graduated he was also becoming known for his community work, starting with his efforts to help at-risk young women at the Henry Street Settlement.

In the 1960s, Mr. Agüeros was part of a group of Puerto Ricans who met informally to discuss the challenges facing residents of East Harlem, the Lower East Side of Manhattan, the South Bronx and Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

In 1968, he was tapped by Mayor John V. Lindsay to be deputy commissioner of the city’s main antipoverty agency, making him the highest-ranking Puerto Rican in city government at the time.

But his tenure lasted only a little more than two months, and he was forced to resign amid reports that he had not filed income tax returns for a few years. Instead of leaving quietly, however, Mr. Agüeros began a five-day hunger strike in his office, demanding that Puerto Ricans be named to city and state boards and agencies in education and housing, and that the city hire Puerto Ricans for professional positions. He ended the protest after several days, after the city acceded to some of his demands.

Mr. Agüeros went on to earn a master’s degree in urban studies in 1970 at Occidental College in Los Angeles. Returning to New York, he went to work at a Lower East Side antipoverty program, remaining there until 1977, when he was asked to be the director of a nascent Puerto Rican museum housed in several storefronts on East 106th Street and Third Avenue.

Within months, he had the idea of moving the museum into a city-owned building on Fifth Avenue, making El Museo del Barrio the northern anchor of the city’s Museum Mile, and putting it in a better position to jockey for city funds. Expanding both the galleries and the collections, he embraced not just the local Puerto Rican community but also the larger Latin American experience.

“We are too culturally rich to force ourselves into ghettos of narrow nationalism,” he said in a 1978 interview. “El Museo now wants to embody the culture of all of Latin America.”

A decade later, clashes over financing with Bess Myerson, who led the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs, resulted in his ouster by the museum’s board. He later earned a living as a grant writer. He also wrote poetry.

Martin Espada, a poet and friend, took notice of those writings and made sure they were published. Mr. Agüeros’s first collection, “Correspondence Between the Stone Haulers,” came out in 1991. It was followed by “Sonnets From the Puerto Rican” and “Lord, Is This a Psalm?”

His verse tackled issues of race, class and city life, and was delivered in a wry tone. “Jack gave those big abstractions like justice, poverty and racism a human face and distilled those issues brilliantly,” said Mr. Espada, whose father, Frank, worked closely with Mr. Agüeros for decades. “He could say in a few words what a sociologist would take 100 pages to say.”

Mr. Agüeros was married three times. Among his survivors are two sons, Marcel and Kadi Agüeros; a daughter, Natalia Agüeros-Macario; and three grandchildren.

Last year, Mr. Agüeros donated his papers to Columbia University. On Monday morning, his son Marcel said his father had long ago decided on one final donation, to an Alzheimer’s research program at Columbia University Medical Center.

“He was part of the brain donation program at the Taub Institute,” Marcel Agüeros said. “As soon as he knew he was sick, he believed he had to try and help as many others as he could. He was always the activist.”